Fisheries officers are carrying out 1,000 fewer annual inspections of commercial vessels and other fisheries-related sites than they were five years ago, new data shows.

Covid-19 has had an impact, but the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) also says inspections are now more targeted following the introduction of a new electronic reporting system in 2019.

BusinessDesk obtained the inspection figures, which cover inspections of commercial fishing vessels, licensed fish receivers and fish dealers, using the Official Information Act (OIA).

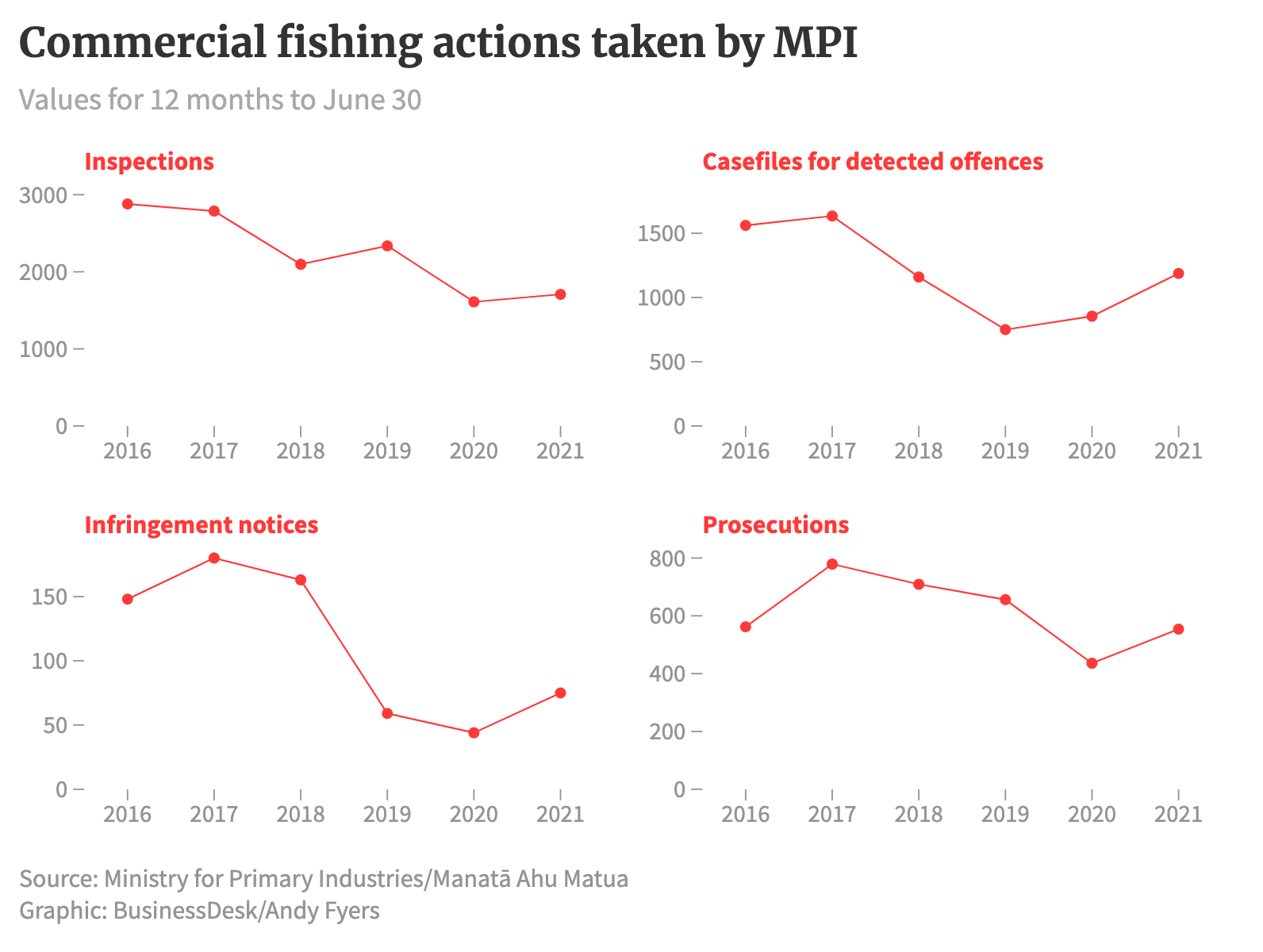

The MPI response shows there were 2,880 inspections in the year to June 2016, falling to just 1,707 in the year to June 2021.

The number of infringement notices being issued is also down, falling markedly from 163 in the year to June 2018 to 59 in the year to June 2019.

The ministry attributed this to the transition from paper to electronic reporting, which was rolled out from Jan 1, 2019. During the rollout period, it moved to an educational approach.

MPI compliance services director Gary Orr said the introduction of electronic monitoring meant MPI had more visibility of commercial fishing activity than ever before.

"Commercial fishing vessels are tracked using global positioning technology in near real-time, which enables us to better target and prioritise physical inspections so that we can direct our resources to where they are most needed,” he said.

If a vessel strayed into a protected area, MPI would be immediately alerted and could take action. If the regulator received a report of fish-dumping, it could quickly narrow its focus to the vessels operating in an area.

"One measure of the effectiveness of this approach is the fact that while the number of investigations have reduced within the period you refer to,” Orr said, “the number of prosecutions has remained relatively stable.”

The figures showed a high of 779 offences that MPI decided to prosecute in the year to June 2017, compared to 554 in the year to June 2021.

MPI noted in its response that cases often involve multiple offences.

Case for cameras

The new reporting system required fishers to electronically record their catch in near real-time. Orr said this had reduced the number of infringements MPI was issuing, as it was more accurate than the old paper-based system, which he described as more prone to errors.

“In addition to these changes, we consider electronic monitoring has incentivised more fisheries compliance overall,” Orr said.

“The coming rollout of cameras on inshore fishing vessels will provide more valuable information to support our decision-making.”

Forest & Bird marine spokesman Geoff Keey agreed the electronic reporting system had made MPI more efficient.

The improvement bolstered the case for the rollout of cameras, he said.

Having cameras onboard commercial fishing boats would deter bad behaviour and lead to more accurate reporting, because MPI could check the reported catch against what the cameras showed, he said.

“We have to remember that fishing is an activity that mostly happens out of sight, out of mind, but it involves the management of the sea.

“What fishers do has a huge impact on what happens in our oceans, so we need to have that transparency.”

The number of fisheries officers hasn’t changed much in recent years.

Orr said as of Jan 2022 there were about 170 officers covering commercial and recreational fishing, as well as supporting MPI’s treaty partners to protect their fisheries.

“In fact, when taking into account the addition of information drawn from electronic monitoring, the overall level of resourcing for fisheries compliance has increased.”