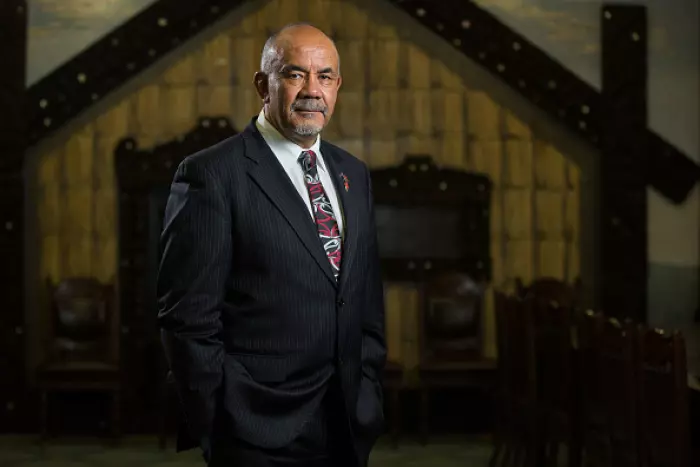

As part of its 'How good is our public sector?' series, BusinessDesk is interviewing former ministers about the crucial relationship between politicians and public servants. Oliver Lewis talks to former Māori development minister Te Ururoa Flavell.

Te Ururoa Flavell has been busy. During the pandemic, the former Te Pāti Māori co-leader has spent time delivering food vouchers to struggling whānau in and around Rotorua. Māori land trusts in the area put up the money – for food and firewood – because the Ministry of Social Development (MSD) wasn’t meeting elevated levels of need, Flavell says.

MSD has money, but funds have largely been flowing to providers who aren’t in contact with the people Flavell has been seeing, he said. And that’s the problem. Whanaungatanga (a relationship through shared experiences and working together which provides people with a sense of belonging) is a key part of te ao Māori, yet too few public service departments and the officials staffing them have spent time developing strong relationships with Māori.

“If you can build those relationships, then things will happen for you,” Flavell says.

“The downside is most of the public sector hasn’t been in that position. They don’t necessarily know how to make those relationships with Māori.”

The inequity of the covid-19 vaccine rollout has provided further evidence of the importance of by-Māori, for-Māori solutions. The day we speak, in late October 2021, Flavell had been preparing for a video to encourage more Māori to get vaccinated.

A few days later, John Tamihere, chief executive of the Whānau Ora Commissioning Agency, won a High Court ruling against the Ministry of Health.

Tamihere had been seeking the personal data of unvaccinated Māori so Māori health providers could go to them. The court ruled the ministry had to rethink its decision to withhold the data with regard to Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Tamihere won a further court ruling in December forcing the ministry to reconsider what it would release.

“Māoridom is in a constant struggle,” Flavell says.

“We are always in a struggle to get simple things like information that would help everybody.”

Flavell, who entered parliament in 2005 and lost his seat in 2017, was minister for Māori development and Whānau Ora from 2014 to 2017 when the Māori party was in coalition with National. He was also associate economic development minister.

As a junior coalition partner, the Māori party relied on National to progress their agenda. A select group of senior National MPs, including John Key and Bill English, were key to getting legislation across the line, Flavell says.

“Without the coalition party leadership, none of it would have rolled.”

Flavell had ministerial responsibility for Te Puni Kōkiri (TPK). He relied on officials within the department, the main policy advisor to the government on Māori development and wellbeing, to provide him with free and frank advice and to keep him safe by making sure he was properly briefed. They largely did, he says, except for one occasion where he took officials to task for providing poor quality advice. It didn’t happen again, he says.

Flavell believes the public is mostly ignorant of the amount of work done by officials to progress new legislation – consultation, language checks, it all takes time. He and his officials spent years working on Te Ture Whenua, a bill to reform Māori land law. It remains a major regret for Flavell that he didn’t try to rush it through before the 2017 election.

“You’re trying to push things faster and faster but the machine is such that – unless you go through it – you don’t realise how much is in behind.”

Risk averse and reluctant

On numerous measures – health, justice and social issues – Māori are overrepresented in negative statistics. Traditional government approaches haven’t worked to ensure equitable outcomes, something the Waitangi Tribunal has spelt out multiple times in decisions against the Crown for failing to comply with Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

In government, the Māori party sought to address this by establishing Whānau Ora, a for-Māori, by-Māori approach to providing health and social services focusing on families.

Flavell secured funding top-ups during his time as a minister, but says more was always needed.

“The idea was to haul resources out of the big agencies – from health, from social development and so on – and put it in Whānau Ora and allow Māori providers to utilise it,” he says.

The issue? Some officials and ministers weren’t used to the approach, Flavell says. They were wedded to the usual ways of doing things and didn’t want to relinquish control.

“Ministers and ministries want to keep their resources and they still believe – they have this view – that they know what’s best for Māori communities. But they clearly don’t.”

Flavell never encountered overt paternalism from officials. Some public servants were great, he says, but others stymied progress through their inaction and unwillingness to listen and engage with other ways of doing things.

As minister for Māori development, Flavell felt his brief extended beyond TPK and economic issues to cover housing, education, justice and Child, Youth and Family (the troubled agency that morphed into Oranga Tamariki). Because he wasn’t the responsible minister, though, his staff sometimes struggled to get information from other departments. It depended on the minister, Flavell says.

To make sure their concerns were heeded, the Māori party would question whether proposed legislation or reforms were Treaty of Waitangi-compliant.

“When we got to that point that was always a hard discussion to have with other ministers and officials because they didn’t quite get it,” Flavell says.

“We were sort of the treaty conscience, if you like, of the National party, because no one else would be.”

Cultural competency wanting

Post-politics, Flavell works as a consultant teaching people, largely in the private sector, about te ao Māori.

When he was a minister, he ran into officials at the highest levels who didn’t know how to relate to and work with Māori. Some did, but Flavell believes the public service is generally short on cultural competency.

The government has acknowledged that, he says, through the work of Te Arawhiti, the office for Crown-Māori relations.

The department has devised a framework and monitoring survey to help build individual and organisational capability across the public service when it comes to tikanga and Crown-Māori relations.

Worksheets include suggestions on how to make workplaces feel comfortable and supportive for Māori, as well as extensive guidance on what different levels of competency look like.

“The ability to interact with Māori in a certain way changes the whole way Māori view agencies,” Flavell says.

“Yet, many people don’t know how to do that because their life experience hasn’t been around interaction with Māori.”

Upskilling the public service will be hard, Flavell believes. But it’s important to do the work, he says, because currently too many Māori feel uncomfortable working in government departments. The culture isn’t conducive to them staying.

People want to work with others who pronounce their name correctly, Flavell says, who get their jokes and understand their culture.

“Māori in those agencies struggle because they know that their people are probably the ones that are suffering most,” he says.

“And yet they’re the most powerless to be able to do something because they aren’t necessarily in those positions of authority to allow them to change the situation.”

For government agencies to be truly treaty-compliant, they need to develop better relationships with Māori, trust more in Māori providers and get better at trying new ways of working.

“It’s happening slowly,” Flavell says. “But it’s really slow.”

Do you know something we should know? Email BusinessDesk's public sector investigation team: [email protected].