By Daniel Knowles

In a modest apartment just off the freeway in Creve Coeur, a suburb of St Louis, Missouri, An’namarie Baker is packing up her son’s possessions. Three weeks earlier, at 3am on July 3, Damion was murdered in a litter-strewn car park south of the Busch Stadium, where the Cardinals play baseball. He had left a nightclub with a woman he had just met to drive her to pick up her car.

According to the detective on the case, a man challenged him, demanding his keys. Instead, Damion fought back, only for more men to emerge and open fire. He was shot eight times, and the woman he was with five. Bullets from three different guns were found at the scene. He died; she survived. Nobody has been arrested.

Educational scholarships

Damion, says his mother, was the perfect child. “Being a mom is my proudest thing,” she says.

She was raised in public housing in St Louis; her first son, Devon, was born when she was just 17. Damion won a scholarship to a Catholic private school, where he joined the American football team, winning the state championship. That earned him another scholarship to Holy Cross, a private university in Massachusetts. On graduating, he set up his own property business, which did well.

A few months before he was killed, he moved into his own apartment, taking along his collection of Pokémon cards. At the age of 25, he liked to play video games, mentor young footballers and read business books. He had never been arrested, or even fingerprinted. He had a habit of correcting people with the words, “Well, technically”.

“I just can’t believe that Damion pulled that ticket,” An’namarie Baker says. His academic and sports brilliance, and his clean record, might have protected him. Yet like thousands of other young black men, he was gunned down in the street, one of 132 people killed so far this year in St Louis, a city of 300,000 people.

In 2021, 199 people were killed, giving St Louis the highest murder rate of any big city in America. Globally, only big cities in Mexico, Venezuela and South Africa record more murders as a share of population: all countries dramatically poorer than the United States.

The body of a homicide victim is loaded into a coroner's van in Oakland, California. (Image: Getty)

The body of a homicide victim is loaded into a coroner's van in Oakland, California. (Image: Getty) According to the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, a federal government agency, there were 24,500 homicides in America in 2020. That was a 28% rise on 2019, the biggest one-year jump in over a century.

Murder rates spiked almost everywhere – in big cities, suburbs and rural areas. There were more victims of both sexes, almost every race and ethnicity, and of every age group. But the fastest-growing number, both proportionately and in absolute terms, was of young black men living in big cities. Of all homicides, 19,350 involved guns. Black people, of whom 12,000 were killed in that year, accounted for 70% of the increase in gun homicides.

More recent data nationwide is not yet available, but city-by-city figures suggest that the spike has not reversed itself. In 2021, Chicago had more than 800 homicides, the highest number since 1994, when America’s previous big wave of violent crime was beginning to subside. The murder rate in black neighbourhoods reached its highest-ever level. New York, although still among the safest cities in America, recorded its most murders in a decade. Cities as far afield as Austin in Texas and Portland in Oregon have passed all-time records for homicide.

So far this year, several cities, including Chicago and New York, have seen their murder rates dip a little. But they remain far higher than before the pandemic. Almost no cities have escaped unscathed. As well as murders, other violent crimes such as carjacking have soared even as less-violent crimes such as burglary have declined.

The murder rate in America is more than six times the levels in Britain, France and Germany, and more than 20 times that in Japan. For every murder, there are more victims who are not killed but may be maimed for life, some carrying bullets in their flesh for years.

The continuing violence throughout the United States has many Americans living in fear for their own lives. (Image: Getty)

The continuing violence throughout the United States has many Americans living in fear for their own lives. (Image: Getty)Young black men suffer disproportionately: around one in 700 aged 18 to 24 were killed in 2020. Studies of Washington, DC, and Los Angeles have found that homicide reduces the average life expectancy of black men by roughly two years. But Americans of all races are murdered more than people in other rich countries. White non-Hispanic Americans are more than three times more likely to be murdered than white Britons are.

A costly business

Such violence does not just cut short individuals’ lives and cause misery to their families. It also makes local residents far more nervous. Older people fear leaving their homes; children are not allowed out to play. Those who have the means abandon once-cherished homes for safer places. As middle-class residents leave, cities can find themselves in a spiral of decline and disinvestment, because less tax has to fund the same public services.

Taking all these into account, calculations made in 2004 put the cost to society of a single murder at US$9.7 million ($16.3 million). That is equivalent to US$15.7m today, and it would put the total cost of homicide in America at nearly US$400b a year, or just under 2% of GDP, most of it concentrated in the poorest parts of the country.

The very public killing of George Floyd by a police officer in May 2020 sparked demonstrations not only in the US but also throughout the world. (Image: Getty)

The very public killing of George Floyd by a police officer in May 2020 sparked demonstrations not only in the US but also throughout the world. (Image: Getty) In 2020, protesters took to the streets of US cities to argue that “Black Lives Matter”. The uprising, sparked by the murder of George Floyd, an unarmed 46-year-old black man, by a Minneapolis policeman, helped to start a debate among progressives about whether policing was even necessary. It also created momentum among moderates for strengthening rules to hold law-enforcement officers to account.

The awful surge in the number of black men killed by people other than the police, however, has taken the wind out of the sails of this discussion. Instead, Democrats like Willie Wilson, a candidate for the Chicago mayoralty, promise to “take the handcuffs” off police and get back to the tough policing of the past.

100,000 more police

In July, President Joe Biden announced US$37b more federal spending on crime prevention, including money to enable local governments to hire 100,000 more police.

This special report argues that reforming policing and the criminal justice system are key to reducing America’s high levels of violent crime. Some contributing factors, such as the ready availability of guns, cannot be fixed by changes to policing. But violent crime, especially in the poorest neighbourhoods most prone to it, could still be sharply reduced. It will not happen unless politicians maintain their support for change.

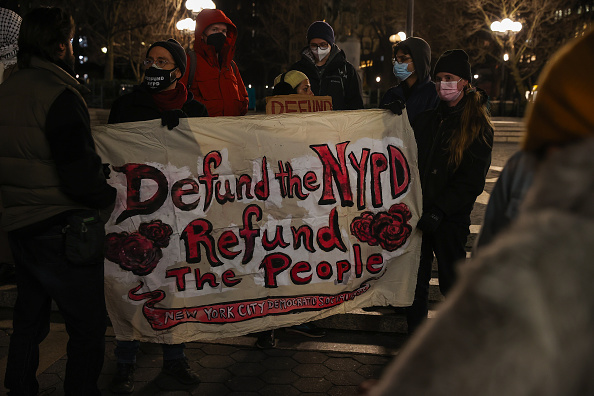

Allegations of brutality made against many US police forces led to a widespread campaign to strip them of their public funding. (Image: Getty)

Allegations of brutality made against many US police forces led to a widespread campaign to strip them of their public funding. (Image: Getty)“Defunding” the police, a leftist obsession that became popular in 2020, is not the answer. But neither is a strategy that reverts blindly to the aggressive, untargeted policing of the past. Better ideas are needed. As An’namarie Baker says, “Why don’t we care more about this? It feels like, as a country, we are allowing this to happen. How are we not doing a better job of curbing this?”

A good way to start answering these questions is to look more carefully at what drives so many to commit murder in the first place.

© 2022 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

From Economist.com, published under licence.

The original article can be found at www.economist.com