For New Zealand’s art community, the 1990s began with a full-on outcry after the then National Art Gallery paid $900,000 for two paintings by CF Goldie that it had had the chance to buy the previous year for $160,000.

Art dealers and auction-house owners Graham Choate and Dunbar Sloane Snr had bought the works from the family of the original owner, the Countess of Ranfurly, wife of a former NZ governor, and sold them by private treaty to the museum. When the transaction was disclosed in the media, the public was outraged, appalled by the missed opportunity to buy them at the substantially lower price. Cue lots of angry letters to the editors of newspapers. At the time, New Zealand was still in the grip of the recession that followed the sharemarket crash of 1987. Now these works – the famous Darby and Joan, depicting Ngā Puhi kuia Īna Te Papatahi, and The Widow: Hārata Rēwiri Tarapata, Ngā Puhi – are the jewels in the crown of the Goldie collection at Te Papa Tongarewa.

In the early part of the decade, despite the tough economic times, the art scene exploded with a large number of galleries popping up in Auckland to join the more established players who had been around since the 1980s, such as RKS Gallery in Wellesley Street.

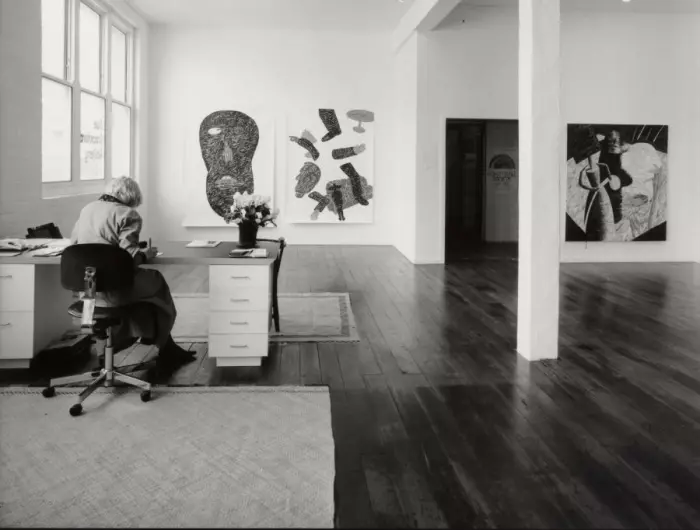

The modern dealer gallery model had been established here by Sue Crockford after she returned to New Zealand and, in 1985, set up shop in Albert Street. She modelled her business on the New York galleries that had a stable of artists who were permanent exhibitors and didn’t move around. Crockford’s gallery – in a character building with high ceilings and lots of light – exuded a sense of style, sophistication and professionalism. She initially represented established artists such as Richard Killeen and Gretchen Albrecht; in later years, younger creatives such as Peter Robinson, John Reynolds and Julian Dashper joined her stable.

Unlike other established galleries in this period which handled a combination of resale artworks and contemporary artists, the new businesses solely represented contemporary practising artists from both New Zealand and abroad.

John Gow, director of Gow Langsford Gallery in Auckland, remembers those times well. He and Gary Langsford had started their business in the late 80s in Grey Lynn, but in the early 1990s had moved into a recently converted heritage warehouse at 123-125 The Strand, alongside Mary Vavasour’s Works on Paper gallery and the Greg Flint gallery. Gow recalls that despite the economic times being tough, sales ticked along fairly regularly.

Gow Langsford also supported their artists, buying painting materials for Allen Maddox and providing a regular salary for Tony Fomison, but the gallery itself relied on patronage from art collectors such as Jenny and Alan Gibbs, Erika and Robin Congreve and Dayle and Chris Mace, who understood the importance of the arts and of the sector’s survival during this period.

In 1992, Gow Langsford moved to their current premises on Kitchener Street opposite Auckland Art Gallery and this revitalised their client base, bringing new collectors.

During this period, Webb’s auction house sold Colin McCahon’s “last painting”, I Considered All the Acts of Oppression, for $503,000, a record for any New Zealand artwork at auction. In a tense bidding battle that involved several Australian institutions, Jenny Gibbs was the victor. Gow Langsford were well placed to capitalise on the interest in McCahon’s work through their relationship with New Zealander Martin Browne, an art dealer in Sydney. They worked closely to jointly promote McCahon’s art on both sides of the Tasman. Resales of his work kept Gow Langsford going during this time and underpinned the business, allowing them to support the contemporary artists in their stable.

Art New Zealand magazine has been chronicling the exhibitions and artists of New Zealand since the mid-1970s and editor/publisher William Dart has been at the helm since 1983, regularly visiting all the galleries. His recollection of the Auckland art world in the 1990s is of a lot of small dealer galleries in the city, all within easy walking distance of one another.

A handful of galleries such as Oedipus Rex (now OREX) and Masterworks still operate today, though in different locations, but in the 90s, there were a number of galleries in Lorne Street, Wellesley Street and High Street, all with vibrant artist stables consisting mainly of Pākehā practitioners. Many were attracted to the area by the opening in 1995 of the NEW gallery in Khartoum Square as an extended exhibition space for Auckland Art Gallery across the road. With an instantly recognisable logo designed by artist John Reynolds, this space displayed contemporary art from both local and international artists and significantly increased the number of people attending exhibitions.

In another area of art publishing, the mid-90s saw prominent collector-turned-gallerist Warwick Brown and art academic Michael Dunn both publish books profiling contemporary artists, most notably 100 New Zealand Paintings and Contemporary Painting in New Zealand. These publications promoted the visual arts in a very accessible way for the general public and are still highly regarded today.

It was during this decade that issues around biculturalism and Māori identity came to the fore and several notable events took place. From 1984-86, the groundbreaking exhibition Te Māori toured the US and enjoyed a rapturous reception. When it returned home in 1987, there was a realisation here that this aspect of our country’s culture had been totally overlooked and undervalued; this was the start of an awakening awareness of New Zealand’s dual identity that grew through the 1990s.

The Headlands exhibition of 1992 was one of the major events to address issues of appropriation in art, something that would become ever more topical as the decade progressed. Headlands brought together a collection of New Zealand artists with the curatorial intention of “thinking through” New Zealand art, but it was overshadowed by a controversy surrounding Gordon Walters.

Walters flew to Sydney for the exhibition opening at MCA (Museum of Contemporary Art Australia), only to find that one of the catalogue essays – written by art historian Rangihiroa Panoho – criticised him for using the koru form as “his own personal signature” and for a “denial of the cultural dimension” within his koru paintings. The art world was divided and much dialogue supporting each side of the argument ensued, including a publication by Richard Killeen and academic Francis Pound supporting Walters’ work.

Later that year, the issue appeared again when provocative artist Dick Frizzell exhibited a body of work, Tiki, at Gow Langsford Gallery which reworked the tiki and manaia motifs in a variety of ways – such as a Picasso still life or Casper the friendly ghost – to resemble high and low art. Coming off the back of Headlands, this was bound to spark controversy and the exhibition catalogue included academic essays both in support of and in opposition to the works. The conversation continued well into the decade.

By the end of the 1990s, the art world in Auckland had changed greatly. There was an air of buoyancy and optimism which foreshadowed the art boom of the early 2000s. The art-buying public were more knowledgeable thanks the arrival of international artists showing at some of the dealer galleries (Sue Crockford showed Daniel Buren and Sol LeWitt and Gow Langsford held shows for Dan Flavin and Donald Judd, among others).

The talent was more diverse; this was the decade that saw a significant increase in the number of Māori and Pasifika artists becoming major players in the contemporary scene. The 1990s were formative years for Shane Cotton, Michael Parekōwhai and John Pule, for example, and they became well recognised during this time.

There were transtasman relationships as well: New Zealand artists had Australian dealers, including Richard Killeen at Ray Hughes Gallery and Laurence Aberhart at Darren Knight Gallery, both in Sydney. Jeffrey Harris was living and working in Melbourne.

This was the decade that expanded and educated the art market and moved New Zealand towards the vibrant and diverse sector it is in the 2020s.

Briar Williams is a fine art valuer at Art Valuations NZ and gallery manager of {Suite} in Auckland.