Electric vehicles (EVs) seem unstoppable. Carmakers are outpledging themselves in terms of production goals. Industry analysts are struggling to keep up.

Battery-powered cars could zoom from less than 10% of global vehicle sales in 2021 to 40% by 2030, according to BloombergNEF, which provides strategic research on the pathways for sectors to adapt to the energy transition.

Depending on who you ask, that could translate to anywhere between 25m and 40m EVs. They, and the tens of millions manufactured between now and then, will need plenty of batteries.

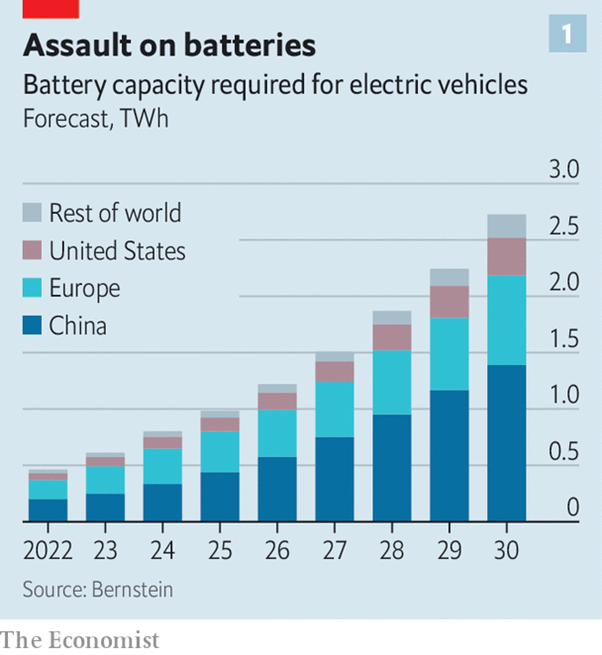

Investment consultancy Bernstein reckons that demand from EVs will grow nine-fold by 2030 (see graphic 1 below) to 3200 gigawatt-hours (GWh). Energy research company Rystad puts it at 4000GWh.

Such projections explain the frenzied activity up and down the battery value chain. The ferment stretches from the salt flats of Chile’s Atacama desert, where lithium is mined, to the plains of Hungary, where on August 12 CATL of China, the world’s biggest battery-maker, announced a €7.3bn ($11.7bn) investment to build its second European “gigafactory”.

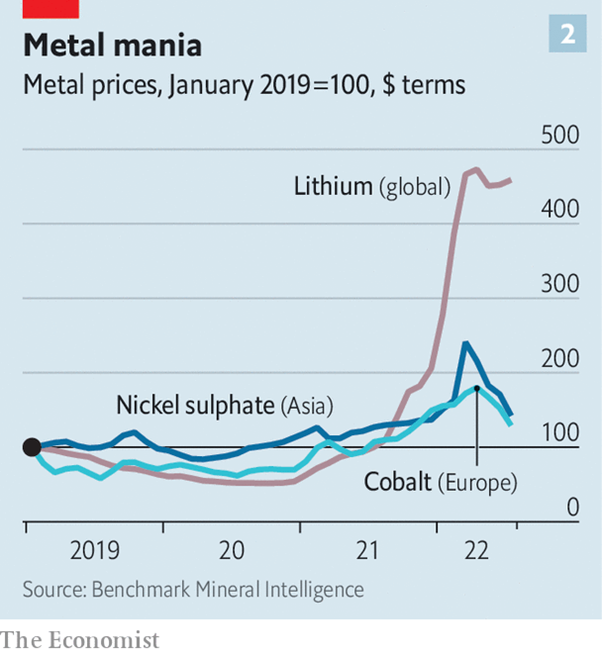

It is, though, looking increasingly as though the activity is not quite frenzied enough, especially for the Western car companies that are desperate to reduce their dependence on China’s world-leading battery industry amid geopolitical tensions. Prices of battery metals have spiked (see graphic 2 below) and are expected to push battery costs up this year for the first time in more than a decade.

In June, BloombergNEF cast doubt on its earlier prediction that the cost of buying and running an EV would become as cheap as a fossil-fuelled car by 2024. Even more-distant targets, such as the European Union's coming ban on new sales of carbon-burning cars by 2035, may not be met. Could the EV boom run out of juice before it gets started?

On paper, there ought to be plenty of batteries to go around. Benchmark Minerals, a consultancy, has analysed manufacturers’ declared plans and found that, if they materialise, 282 new gigafactories should come online worldwide by 2031. That would take total global capacity to 5800GWh. It is also a big “if”.

Bernstein calculates that current and promised future supply from the six established battery-makers – BYD and CATL of China; LG, Samsung and SK Innovation of South Korea; and Panasonic of Japan – adds up to 1360GWh by the end of the decade The balance would have to come from newcomers – and being a newcomer in a capital-intensive industry is never easy.

The optimistic overall capacity projections conceal other problems. Matteo Fini of S&P Global Mobility, a consultancy, notes that gigafactories take three years to build but require longer – possibly a few extra years – to manufacture at full capacity.

As such, actual output by 2030 may fall short. Moreover, manufacturers’ unique technologies and specifications mean that cells from one factory are usually not interchangeable with those from another, which could create further bottlenecks.

Chinese dominance

Most troubling for Western carmakers is China’s dominance of battery-making. The country has close to 80% of the world’s current cell-manufacturing capacity. Benchmark Minerals forecasts that China’s share will decline in the next decade or so, but only a bit – to just under 70%. By then, America would be home to just 12% of global capacity, with Europe accounting for most of the rest.

Americans’ slower uptake of EVs may ease the crunch for carmakers there. Deloitte, a consultancy, expects the US to account for just under 5m of the 31m EVs sold in 2030, compared with 15m in China and 8m in Europe.

Big American carmakers already have joint ventures with the big South Korean battery producers to build domestic gigafactories. In July, Ford and SK Innovation finalised a deal to build one in Tennessee and two in Kentucky, with the carmaker chipping in US$6.6bn and the South Korean firm US$5.5bn. The same month, the Detroit giant struck a deal to import CATL batteries. General Motors and LG Energy are together putting over US$7bn towards three battery factories in Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee.

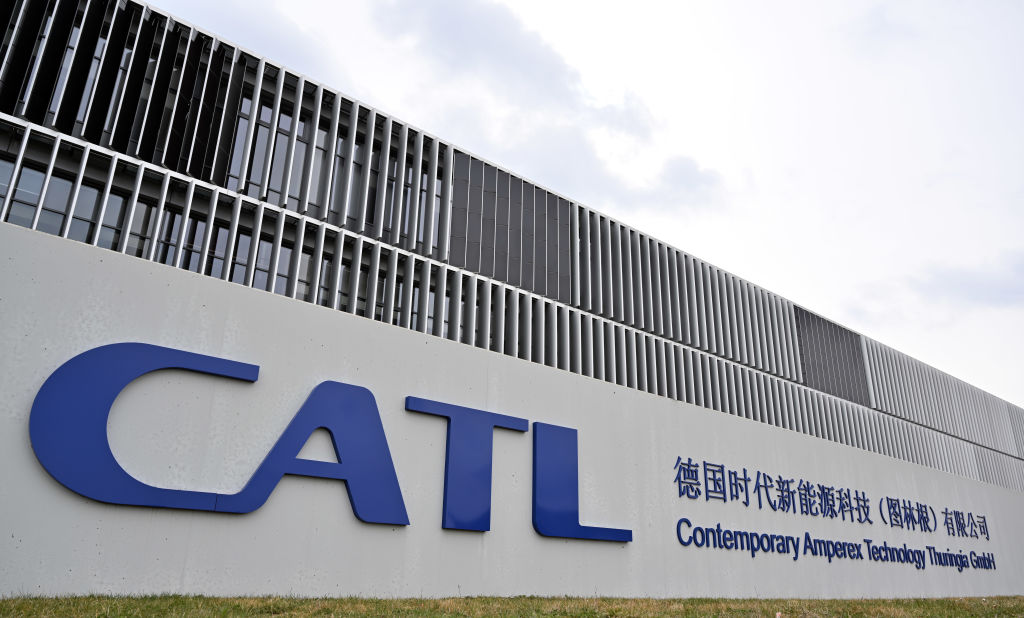

Chinese corporation CATL has invested €1.8bn ($2.9bn) in developing a giant battery-manufacturing facility in Thuringia, Germany. (Image: Getty)

Chinese corporation CATL has invested €1.8bn ($2.9bn) in developing a giant battery-manufacturing facility in Thuringia, Germany. (Image: Getty)A number of European startups, such as Northvolt of Sweden, which is backed by Volkswagen and Volvo, are also busily building capacity.

Yet the continent’s car industry looks likely to remain quite reliant on Chinese manufacturers. Some of those batteries will be manufactured locally: CATL's first investment in Europe, a battery factory in Germany, is set to begin operations at the end of the year. Some packs or their components may, however, still need to be imported from China.

That is not a comfortable position to be in for European carmakers. It may become even less so if the EU introduces levies based on total lifecycle carbon emissions from vehicles, including electric ones.

Northvolt’s chief executive, Peter Carlsson, reckons that proposed EU tariffs on carbon-intensive imports could add 5-8% to the cost of a Chinese battery made using dirty coal power. That could be roughly equivalent to an extra US$500, give or take, per pack.

Such rules would boost his firm’s prospects, since it runs on clean Nordic hydroelectricity. It would also severely limit European carmakers’ ability to source batteries from abroad.

What’s mined isn’t yours

These manufacturing bottlenecks, serious though they are, look more manageable than those at the mining end of the battery value chain.

Take nickel. Thanks to a big production increase in Indonesia, which accounts for 37% of global output of the metal, the market seems well supplied. However, Indonesian nickel is not the high-grade sort usable in batteries. It can be made into battery-compatible stuff, but that means smelting them twice, which emits three times more carbon than does refining higher-grade ores from places like Canada, New Caledonia or Russia.

Those additional emissions defeat the purpose of making EVs, notes Socrates Economou of Trafigura, a commodities trader. Carmakers, particularly European ones, may shun the stuff.

Cobalt has become less of a pinch point. A price spike in 2018 prompted battery-makers to develop battery chemistries that use much less of it. Planned mine expansions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), home to the world’s richest cobalt deposits, and Indonesia should also tide battery-makers over until 2027.

Western car manufacturers are reluctant to deal with mining firms in the Democratic Republic of the Congo until verifiable improvements are made to working conditions. (Image: Getty)

Western car manufacturers are reluctant to deal with mining firms in the Democratic Republic of the Congo until verifiable improvements are made to working conditions. (Image: Getty)Most uncertainty concerns lithium. A shortage is forcing manufacturers unable to get their hands on enough of the metal to cut production. For now, consumer-electronics firms are bearing the brunt. But the smaller batteries in electronic gadgets only represent a fraction of demand. EV makers, whose battery packs use a lot more, could be next.

By 2026, the lithium market is projected to tip back into surplus, thanks to planned new projects. However, most of these are in China and rely on lower-grade deposits which are much costlier to process than those of Australia’s hard-rock mines or Latin America’s brine ponds.

Economou estimates that a price of US$35,000 per tonne of the battery-usable form of lithium carbonate is required to make such projects worthwhile – lower than today’s lofty levels, but three times those a year ago.

The high-grade stuff due to come from elsewhere should not be taken for granted, either. Chile’s new draft constitution, which will be put to a referendum next month, proposes nationalising all natural resources. Changes to the tax regime in Australia, which already has some of the highest mining levies in the world, could deter fresh investments in “green” metal production. In late July, the boss of Albemarle, the largest publicly traded lithium producer, warned that, despite efforts to unlock more supply, carmarkers faced a fierce battle for the metal until 2030.

Hard to enforce contracts

Because building mines takes anywhere from five to 25 years, there is little time left to get new ones up and running this decade. Big mining firms are reluctant to get into the business. Markets for green metals remain too small for mining “majors” to be worth the hassle, says the development boss at one such firm.

Despite their reputation for doing business in shady places, most lack the stomach to take a gamble on countries as tricky as the DRC, where it is hard to enforce contracts.

Smaller miners that usually get risky projects off the ground cannot raise capital on listed markets, where investors are queasy about the mining industry, which is considered risky and, ironically, environmentally unfriendly.

The resulting dearth of capital is attracting private-equity firms – often founded by former mining executives – and manufacturers with a newfound taste for vertical integration. LG and CATL are among the battery producers which have backed mining projects.

EV manufacturers such as General Motors and Tesla are paying big money to secure supplies of lithium, a key component in their vehicles’ batteries. (Image: Getty)

EV manufacturers such as General Motors and Tesla are paying big money to secure supplies of lithium, a key component in their vehicles’ batteries. (Image: Getty)Since the start of 2021, carmakers have made around 20 investments in battery-grade nickel, and five others in lithium and cobalt. Most of these projects involved Western firms.

In March, for example, Volkswagen announced a joint venture with two Chinese miners to secure nickel and cobalt for its EV factories in China. Last month, General Motors said it would pay Livent, a lithium producer, US$200m upfront to secure lumps of the white metal. The American EV champion, Tesla, is signing deals left and right.

Mick Davis, a coal-mining veteran now at Vision Blue Resources, an investment firm that invests in minor miners, doubts that all this deal-making will be enough to plug the funding gap. Recycling, which usually makes up a quarter of supply in mature metals markets, is not expected to help much before 2030. Tweaks to battery designs may moderate demand for the scarcest metals somewhat, but at the risk of lower battery performance. Lithium, in particular, will remain hard to substitute. Technologies that do away with it entirely, such as sodium-based cathodes, are a long way off.

Helter-smelter

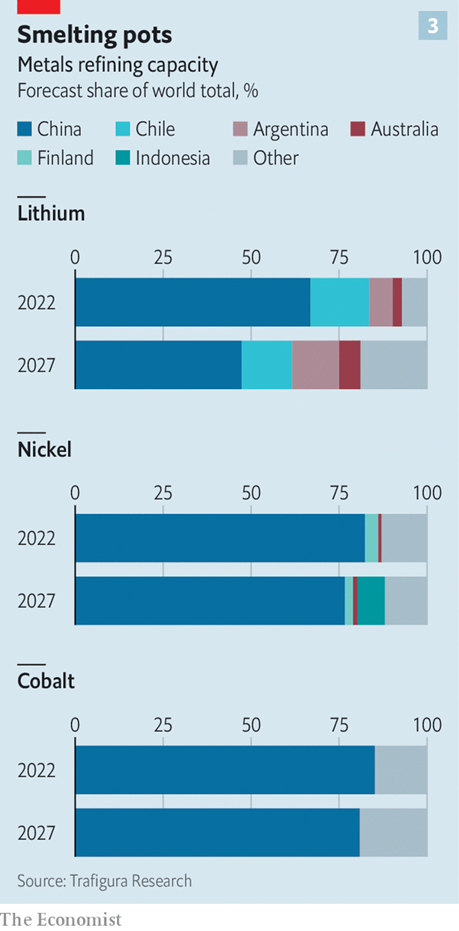

Even if the West’s EV industry somehow managed to secure enough metals and battery-making capacity, it would still face a giant problem in the middle of the supply chain, refining, where China enjoys near-monopolies (see graphic 3 below).

Chinese companies refine nearly 70% of the world’s lithium, 84% of its nickel and 85% of its cobalt. Trafigura forecasts that the shares for the last two of these will remain above 80% for at least the next five years. And as with battery manufacturers, Chinese refiners gobble up dirty coal-generated electricity.

On top of that, according to Trafigura, both European and North American firms are also expected to rely on foreign suppliers, often Chinese ones, for at least half the capacity to convert refined ores into the materials that go into batteries.

Western governments say they understand the urgent need to diversify their suppliers. Last year, American president Joe Biden unveiled a blueprint to create a domestic supply chain for batteries. His mammoth infrastructure law, passed in 2021, set aside US$3bn for making batteries in America.

The Inflation Reduction Act, which Congress passed on August 12, also includes sweeteners for the battery industry, contingent in part on mining, refining and manufacturing components at home or in allied countries.

The EU, which created a bloc-wide battery alliance in 2017 to coordinate public and private efforts, says €127bn ($205bn) was invested last year across the supply chain, with an additional €382bn ($615bn) expected by 2030. Most of this is likely to land downstream, helping Europe and America to become self-sufficient in the production of finished cells by 2027.

That is something. And it remains possible that enough discoveries of new deposits, more efficient mining technology, improved battery chemistry and sacrifices on performance all combine to bring the market into balance.

More likely, as Jean-François Lambert, a commodities consultant, puts it, the EV industry is “going to be living a big lie for quite some time”.

© 2022 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

From Economist.com, published under licence.

The original article can be found on www.economist.com.