The art world has seen significant changes in the past 18 months since covid-19 drastically reshaped the way clients look at and purchase art, but the biggest change has been in the emergence of NFTs and their shift into more mainstream art channels.

NFT stands for “non-fungible token”. Applied to the art world, this concept can initially be difficult to understand as it is so far removed from the traditional artistic media we are familiar with. In this context, an NFT is a digital artwork – it can be a moving image like a GIF or a static image like a JPEG – which is paid for with the cryptocurrency Ether via online marketplaces such as Nifty Gateway* or MakersPlace.

Each work is sold with a digital token that certifies the work purchased is the original or an authentic image (this is the non-fungible part) and the transaction is stored in an online register (the Ethereum blockchain, a rival platform to Bitcoin), which records the owner of the work and any future sales of it in a secure way.

Physical money and cryptocurrencies are “fungible”, meaning they can be traded or exchanged for one another. They’re also equal in value: one dollar is always worth one dollar, one bitcoin is worth one bitcoin. Something that is non-fungible means it has a unique value set by the highest bidder. One painting by Picasso will never be worth exactly the same as another Picasso painting and NFTs work in the same way because the file has a digital signature (the token) that makes it impossible to be exchanged for or equal one another.

Artists who want to sell their work as NFTs have to sign up with a marketplace, then “mint” digital tokens by uploading and validating their information on a blockchain (typically Ethereum). Doing so usually costs $40 to $200. They can then list their piece for auction on an NFT marketplace such as the ones mentioned above. To buy an NFT artwork, you need to decide what marketplace you want to purchase it from and then make sure you have a digital wallet (to store your tokens and your cryptocurrency). Finally, you’ll need the cryptocurrency to pay for your purchase.

NFTs have been one of the art world’s great disruptors and all disruptive events rely on things being done differently. In this case, one of the greatest changes has been to the creators and buyers of the NFT. Until this point, a successful artist would usually need formal art school training and the backing of a reputable gallery and public institutions to forge a career that would earn them the type of money that some NFTs are selling for.

By comparison, many NFTs are being created by graphic designers, digital content creators, animators, and even celebrities with no formal art training or background. These creators are fed up with their work being used on platforms such as Instagram and Facebook without much, if any, financial gain for themselves. The creation of an NFT allows the artist to build in a payment back to themselves if the work is resold in the future (like a resale royalty scheme already in operation in the non-digital art market internationally), and they have the flexibility to sell the work themselves without having a gallery intermediary.

The NFT market has also opened the doors to non-traditional art buyers, and some of the earlier adopters were people who were well versed in trading cryptocurrency, and speculators who were looking for alternative asset classes.

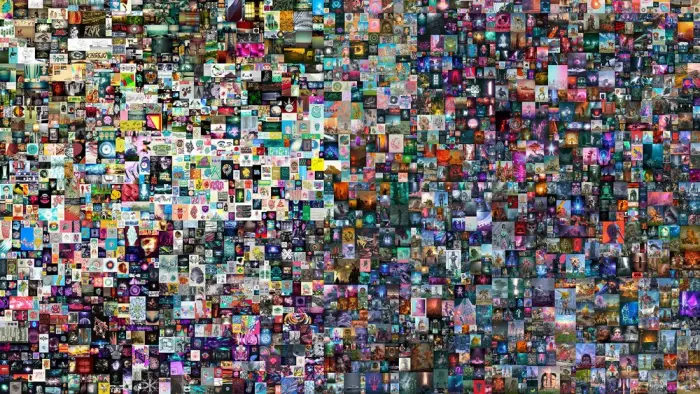

NFTs have been around since 2014 but it’s only been in 2020-2021 that prices in the millions have been paid more regularly. Unsurprisingly, the buyers have been major cryptocurrency investors such as MetaKovan, a Singaporean-based programmer who owns a crypto fund called Metapurse and purchased Beeple’s Everydays – The First 5000 Days (a collage of 5000 digital images, pictured above) at Christie’s in March this year for US$69 million.

NFTs have also opened the door to much younger collectors who have grown up with the internet and are comfortable operating purely online, attracted by the low price point of entry and the democratic feeling of art purchasing.

The mass appeal to non-traditional art collectors comes from the NFT aesthetic. Many have a futuristic or sci-fi feel, many are moving 3D images, the colour is often bright and jarring and the images can reflect popular culture and events (a 20-second video of a nude Donald Trump fighting a nude Joe Biden in mid-air sold recently for US$6.6 million). As well, it’s pretty much as far away from the rarefied world of a traditional art gallery as you can get. In fact, most of the art sold as NFTs would be seen as tacky or kitsch within the regular art world.

So, if a digital image is in essence a file that can just be copied or downloaded by anyone who finds it on the internet, what has fuelled the boom in NFTs? It’s the same principle that underpins regular asset collecting – the opportunity to own the single, authentic piece. To put it in terms of regular art collecting, anyone can own a print of Monet’s waterlilies but only one person or institution can own the original work. In the case of an NFT, you can’t even have it on your wall – it lives on your computer or your phone.

In next month’s art-investing article for BusinessDesk, I will look at the market for NFTs and how they have infiltrated the mainstream through sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s, and investigate whether the rampant growth in this area is a bubble that is about to burst.

*Nifty Gateway is one of the only platforms that allows a client to purchase an NFT using regular currency via a credit card, but the record of the transaction is still stored on the Ethereum blockchain.

Briar Williams is a fine art valuer at Art Valuations NZ