The announcement on Nov 5, 1990, that the Bank of New Zealand (BNZ) had further bad-loan problems and was establishing the Adbro “bad bank” structure had a devastating impact on the company’s share price.

It plunged from 72 cents on the day before the announcement to a low of 44 cents on Dec 6, giving the country’s largest trading bank a market value of just $632 million.

There were two main reasons for the 39% share-price decline:

• Chairman Syd Pasley had been talking up the BNZ’s performance, particularly his comment at the July 1990 annual meeting that the bank had refocused on its core businesses and “this has strengthened the quality of the bank’s balance sheet”.

• The Adbro structure was a shonky money-go-round that delivered considerable benefits to the two major shareholders, the crown and Fay, Richwhite. All other shareholders were excluded from the Adbro structure, which should have been subject to minority shareholder approval, but the NZX granted a waiver from this requirement.

Late 1990

The response of the media and public to the Adbro structure was also extremely negative.

Pasley spent a great deal of time “correcting public confusion” about the structure. He criticised journalists, analysts and shareholders when they implied that the “bad bank” structure had benefited the crown and Fay, Richwhite at the expense of minority shareholders.

On Nov 26, he said: “The major shareholders agreed to contribute $720 million without requiring a contribution from minorities, but they have done so in a way which minimises the dilution of existing shareholders’ positions.”

This $720m contribution was as follows:

| Contributions to Adbro/BNZ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Adbro contribution | $m | ||

Crown | 420.5 | ||

Fay, Richwhite | 50.0 | ||

Capital raising |

| ||

Crown | 140.0 | ||

Fay, Richwhite | 110.0 | ||

Total | 720.5 | ||

Pasley later revealed in a letter to me, as a BNZ shareholder, that Fay, Richwhite had effectively borrowed its $50m contribution to Adbro from the BNZ.

In addition, as part of the deal, Fay, Richwhite sold $60m worth of ordinary shares to the crown and acquired $110m worth of BNZ convertible preference shares, a net investment of only $50m.

The 11% a year paid to Fay, Richwhite on its convertible preference shares was non-deductible to the bank and tax free to Fay, Richwhite. This was a wealth transfer from the BNZ to Fay, Richwhite, and the elimination of at least $578.5m of BNZ tax losses was a wealth transfer from the bank to the crown.

The new National government, which was elected on Oct 27, 1990, was under intense public pressure to initiate an external inquiry into the bank. Finance minister Ruth Richardson refused, but flew to Christchurch on Thursday, Nov 22, to meet the BNZ board and encourage it to undertake an internal inquiry.

She continued to emphasise that the new government would sell the BNZ, as originally outlined in the National Party’s 1987 election manifesto. Her main issue was timing, as the international banking sector remained fragile in the aftermath of the 1987 global sharemarket crash.

Richardson was later quoted as saying: “All actions taken by the government have been designed to protect and enhance the taxpayers’ investment in the BNZ.”

It was hard to argue with this statement as the crown was clearly putting its own interests ahead of minority shareholders who had paid $1.75 a share in the March 1987 IPO.

1991 & early 1992

The BNZ reported a net operating profit after tax of $131.9m for the March 1991 year, with Pasley noting that “the bank, the board and management team are now able to look ahead with considerable confidence”.

It reported a net profit of $171.1m for the year ended March 1992 after a $46m provision for doubtful debts. The net-profit figure was $74m lower than it could have been as the BNZ had to make a New Zealand tax provision of $74m after its tax losses had been transferred to the crown as part of the Adbro arrangement.

The bank remained in the headlines, with Winston Peters, then the National MP for Tauranga, continuing to call for a public inquiry into the Adbro bailout.

In late June, he used parliamentary privilege to claim that Michael Fay was involved in a serious breach of the Companies Act regarding a BNZ loan to fund the construction of the Fay, Richwhite Tower at 151 Queen St, Auckland, now known as the SAP Tower.

Fay and Pasley totally rejected Peters’ claim, but the National MP continued to clash with Richardson, his own party’s finance minister, over numerous issues relating to the BNZ and Fay, Richwhite.

Meanwhile, the bank’s share price had picked up from its Dec 1990 low of 44 cents, but it still remained relatively depressed at 60 cents on Dec 31, 1992, and 71 cents on June 30, 1992.

At this stage – mid-1992 – the BNZ board consisted of: Pasley (chairman), Robin Congreve (deputy chairman), Lindsay Pyne (managing director), Fay, Kerry McDonald, Geoff Ricketts and David Sadler.

Takeover offer

The endgame to the long-running BNZ saga began in earnest on July 21, 1992, when National Australia Bank (NAB) announced a takeover offer at 80 cents per ordinary share and 95 cents for each convertible preference share. This compared with the 70-cents-per-ordinary-share placement to the crown in late 1990 and the issue of convertible preference shares to Fay, Richwhite at 84 cents each.

The offer valued the BNZ at $1.5 billion.

Fay, Richwhite (25.7% shareholder) and the crown (58.4%) immediately announced they would accept the offer. The crown’s statement noted: “Today’s announcement marks the end of an extensive worldwide search for potential buyers of the BNZ. Parties were approached in Europe, North America, Asia and Australasia. The sale of BNZ is another positive step in the successful rebuilding process undertaken by the bank since its recapitalisation in 1990.”

There was huge opposition to the bid, particularly the price, although it would have been very difficult to stop NAB moving to compulsory acquisition as the crown and Fay, Richwhite had agreed to accept in respect of their combined 84.1% shareholding, and 90% is the trigger point for compulsory acquisition.

There were several points of contention, including the appointment of the Sydney-based merchant bankers Baring Brothers Burrows & Co as the independent advisers. It would have been far more appropriate to have a New Zealand-based independent adviser with a deeper understanding of the domestic economy, its business sector and the banking industry.

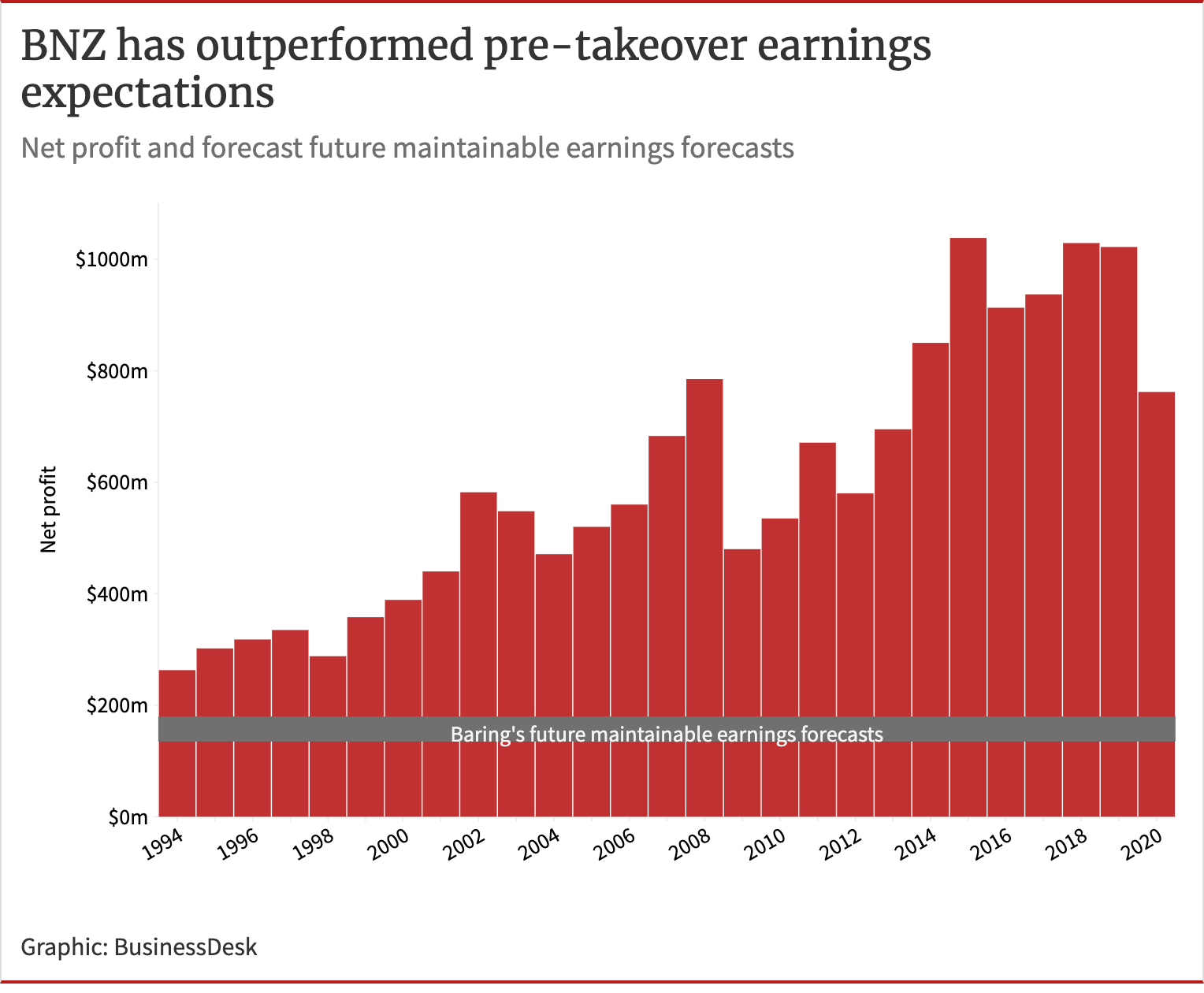

Another contentious point was that Baring’s valuation was based mainly on its assessment that the bank’s future maintainable earnings would be between $135m and $180m a year.

That range was clearly too low as the bank had made substantial bad-debt provisions in previous years, it had dramatically reduced costs as illustrated in part 3 of this series, and it was benefiting from the deregulation of the finance sector.

It was a bizarre takeover process as Pasley, who was an independent director, and Baring, which was supposed to be acting on behalf of minority shareholders, attacked minority shareholders who questioned the maintainable earnings forecast and Baring’s capitalisation of earnings valuation, which was between 71 and 76 cents per ordinary share.

Baring claimed that alternative future maintainable earnings forecasts were “misleading”, “highly inaccurate” and contained “errors”.

Complaints were lodged with the NZX and the Securities Commission, with Baring required to release a supplementary independent report, and the State of Wisconsin Investment Board, which owned 28.5 million BNZ ordinary shares, adopting particularly aggressive opposition to the 80-cents-a-share offer.

Kathleen Harris, the Wisconsin Investment Board’s international portfolio manager, wrote to the Securities Commission to raise her concerns about the relationship between the crown, Fay, Richwhite and NAB. Her concluding comment was: “We are concerned that the independent directors of the BNZ, as appointees of the crown, are unable to adequately represent our interests as minority shareholders.”

Harris made a high-profile visit to New Zealand to argue her case but a standard response from Pasley and Baring was that if shareholders didn’t accept the 80-cents-a-share offer, it was possible that the shares could trade within a range of 55 and 70 cents.

This short-term share-price argument was highly unsophisticated, particularly in relation to a company that was then 131 years old and the country’s largest trading bank.

In spite of huge opposition, NAB reached 90% in early Nov and quickly moved to compulsory acquisition.

Pyne resigned as the BNZ’s managing director, effective Nov 20, and the bank delisted on Dec 21, 1992.

National Australia Bank had acquired BNZ at its third attempt, the first being in late 1988 and the second in early 1989.

Future maintainable earnings

A major contention during the acrimonious takeover offer was Baring Brothers’ future maintainable earnings prediction of between $135m and $180m. The bank didn’t release any detailed prospective financial information and Baring didn’t provide a line-by-line breakdown of its maintainable earnings forecast, with the notable exception that the BNZ’s bad-loan provisioning was expected to be between $75m and $90m a year.

The following table shows that Baring’s forecasts were far too low; the BNZ’s lowest net-profit-after-tax figure following the NAB acquisition was $263m for the Sept 1994 year. This compared with Baring’s predicted high of $180m.

Baring’s bad-loan provisioning forecast, of between $75m and $90m a year, was ridiculously high as the BNZ had switched its focus from high-risk corporate lending to the low-risk retail market.

The BNZ’s highest annual bad-loan provisioning in the decade after the NAB acquisition was $33m and its total provisioning over this 10-year period was a positive $242m, compared with Baring’s total 10-year range between a negative $750m and a negative $900m.

The BNZ reported a positive bad-debt provisioning figure in the decade to 2003 because it recovered loans that had been written off after the 1987 sharemarket crash.

If Baring had accurately forecast the actual net-profit figures for the three years 1994 to 1996, it would have assessed the BNZ’s fair value to be in the $1.35 to $1.40 per ordinary share range, rather than the 71 to 76 cents figure in its independent evaluation.

The BNZ was a fantastic purchase for NAB because the New Zealand bank is probably worth between $15b and $20b at present and the Australian owner has received $10.5b in dividends over the past 28 years. This represents total value of between $25.5b and $30.5b to NAB, compared with its $1.5b purchase price.

We often refer to the great value created by Port of Tauranga (listed in 1992), Mainfreight (1996) and Ryman Healthcare (1999), but the loss in value through the sale of the BNZ has been greater than the positive contribution made by these three companies.

NAB purchased the BNZ at a discounted price and the acquisition represented a massive transfer of value from New Zealand to Australia over the following three decades.

Aftermath

One of the most bizarre developments after the successful takeover of the BNZ was the July1993 announcement that the crown was selling New Zealand Rail to a Fay, Richwhite-led consortium. This was just seven months after Fay, Richwhite sold its BNZ stake to NAB.

The NZ Rail deal indicated that the Treasury was out of its depth as far as the privatisation process was concerned as it allowed Fay, Richwhite to be an adviser to the crown’s asset-sales programme as well as a purchaser of these assets.

The Fay, Richwhite consortium generated huge profits from its NZ Rail investment, partly through financial engineering, but the public didn’t fare as well.

The rail company, which had changed its name to Tranz Rail, had an IPO at $6.19 a share in mid-1996.

Fay, Richwhite sold its shareholding in two main tranches, in 1999 and early 2002. The second tranche involved the sale of 17.5m shares at $3.94 each in February 2002, just over 12 months before Tranz Rail’s share price plunged to 40 cents.

The average cost of Fay, Richwhite’s Tranz Rail shares is estimated to be around 20 cents, compared with the $6.19-a-share IPO price.

Later, Midavia, which was owned by David Richwhite and Michael Fay, agreed to pay $20m to settle a long-running insider-trading case relating to this Feb 2002 Tranz Rail sale, although there was no admission of guilt.

Ironically, Midavia was included in the structure of companies that allowed Fay and Richwhite to make a fortune from the Telecom privatisation.

Looking back: David Lange, Roger Douglas, Ron Brierley and the BNZ

Looking back: BNZ Part 2: Rob Campbell, Frank Pearson and the bank

Looking back: BNZ Part 3: Lindsay Pyne, Michael Fay and the bank

Looking back: BNZ Part 4: Capital Markets, Fay, Richwhite and the bank

Looking back: BNZ Part 5: The Winebox company and the bank

Looking back: BNZ Part 6: The bank adopts Fay, Richwhite proposal

Disclosure of interests: Brian Gaynor is a non-executive director of Content Limited, the publisher of BusinessDesk, and of Milford Asset Management.

[email protected]