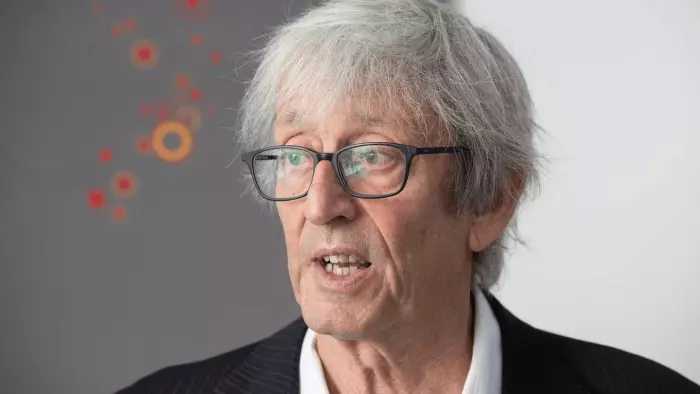

The Wellington Company, the property firm that Ian Cassels leads with his partner, Caitlin Taylor, is spearheading the $500 million housing, retail and commercial development at Shelly Bay (Marukaikuru) and has been behind projects such as Spark Central and Todd Tower. Cassels jumped into the property world in 1990 at a time when, he says, his personal life had become “tumultuous”, property prices were tanking, and he saw an opportunity to change his career as well as his life. He grew up with three brothers – with whom, he says, he was in frequent competition and who all bullied each other mercilessly – and has four sons named Alex, Andrew, Ptolemy and Euripides. His nine grandchildren do include a smattering of granddaughters in the mix.

When I was about seven or eight, I wanted to be prime minister, just so I could do things. My grandfather had died a little bit earlier and I don't know what that had to do with it, but I just thought, "Bloody hell, I'd like to be prime minister."

I was one of four boys, so naturally, I went out of my way to compete and be more glorious than any of them. I was number three in the sibling ranks. Third is always a precious little pup and they want to quietly take out the others – and take the oldest out, too – without telling them they're coming.

My parents were Kiwis and I spent the first five years of my life in Nottingham, England. We came back to NZ because my lungs weren’t too hot and they thought I might survive better here. But when we arrived, even though our parents were Kiwis, we felt a little bit like aliens for quite a while.

We were constantly trying to get used to the NZ way of doing things. The sun was quite bright, so it was a funny country to be in. And we used to say if we had a bloody TV, we would have fewer problems.

We finally got a K9 model Philips brand. My oldest brother, Winton, wrote out a performance contract dictating what we’d do and how’d we behave once we got it. He was very cunning. But, of course, all those promises immediately went out the window once we got the TV.

That feeling of “this isn't home” plagued me for about four or five years after moving here. It has made me believe you should never move children at the age of five as it’s so dislocating.

I missed everything from Nottingham – even our bloody coal cellar. The move made me romanticise things that weren't even good about the place, like mist in the evenings.

And then you come to Wellington and you’re met with the bright sun and the howling winds. It was like there were always burglars outside. It felt like a frightening place.

The other kids weren’t pleasant, either, because we got sent off to school wearing ties, which wasn't the right thing to do. They were pretty merciless at us and we got scragged.

What did I do after leaving school? Drugs and all sorts and pressing the boundaries. I went to university, but I never really attended. I played cards, and I played against genius people. I was in awe of them all, but I played far too much poker.

All that card playing meant I took six years to finish my philosophy and maths degree. And I did most of it in the last two years of study. Why? Well, I saw my younger brother's friends getting degrees and it was just too hard to take, so I went into overdrive.

After uni, well, it was a pretty hard, long slog. Worse than coal mining in Wales. I got sucked into my brother Alasdair’s sandblasting and spray-painting business. Alasdair and I used to verbally tussle regularly, and he got to the point of calling me a professional labourer.

It took a long time to get away from being a professional labourer. I was born in 1953, so I really only got out of that by 1990. I had a fairly tumultuous time in 1990, which made me get back into thinking about going harder, faster, better, and performing much more than I was used to.

It was hard starting from scratch, but at that stage I was already up to six cans of Foster's and a bottle of whisky on the couch a night. And while I didn't give up the whisky and Foster's, I did get off the couch as I had to work hard.

God, I've had so many wonderful successes. There are a whole lot of things I’m happy about but getting Shelly Bay in Wellington a go is one of them. And the connecting part of that is the wealth and the drive and the success that will go to Taranaki Whānui. That's a pretty good thing to be proud of.

I wouldn't say I believe in God, but I do believe in reciprocal goodness. I think if you behave well and if you're reasonably open about celebrating and being grateful for things, it probably goes around.

I have four boys and thankfully they don’t have the same dynamic as my brothers and I did. There are two lots of two, so they don't get into that sort of cross struggling and changing poses and picking on each other.

I say I’m six foot two and three-quarters because I'm precious. And I wanted to be better than the six foot two and a half that Alasdair was.

It's almost impossible to relate property developers to each other, but there is a common thread – which is they're usually more optimistic than they should be. But they're usually trying to do more than somebody else and they're usually short of the money that is required to do it and so they're always trying to make ends meet. They take risks, but they're the optimists of our society. But in this current recession, young developers and old developers are going to be squashed. And that’s a huge loss.

Stress is usually caused by an imposter. The imposter usually goes away and it's usually time-contingent or condition-contingent. You'll find incidents that have come and gone that have been blown out of all proportion because you fear them. Like a dental nurse. So I just don't fear things that much.

When I'm thinking about something quite hard if I walk down Lambton Quay, I can usually find three people, and one or two of those people will be thinking about the same thing that I am and tell me what the answer is or what part of the answer is. All from a walk.

I've taken to swimming in the ocean, which is quite good fun, but it's not actual swimming, because the lungs aren't good. I just wave my arms around 500 times.

My brother Winton died of MS a while back. He used to be a bit of a drinker and travelled the world. He was so clever. Everything that happened, he always asked the reason why.

Ross, my younger brother, died tragically when he was just under 50 of a heart attack. He never really got on top of life.

Alasdair died last year. He was well known as the founder of Cassels Brewing Company. Sometimes it's hard to believe that some little twirpy NZ company that Alasdair founded managed to win the top prize in its category [milk stout] at the World Beer Awards two years in a row.

I always take the weekends off. The only thing that makes me sane is that I sometimes spend quite a bit of the early morning awake. But on the weekends I sleep like a pumpkin.

When I used to drink like a fish, sleeping was always easy. I used to go home on Friday night and drink wine and that was always quite fun. But my liver and kidneys can't take too much more of that.

I've got an addictive personality. It took me about a year and a half to give up smoking. So when it came to giving up drinking, I knew it was going to be really hard – and it was.

I used to drink a lot at events – the key was to drink yourself stupid so you and other drunk people trust each other better when you meet the next day and neither of you remembers what exactly went wrong.

What’s the worst alcoholic drink I’ve ever had? I don’t know, but I’ve probably had them all.

As told to Ella Somers.

My Net Worth interviews may be edited for clarity.