Lockdowns and strict borders measures will remain with us until at least 90% of the population five and older is fully vaccinated.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern didn't spell it out in exactly those terms when she introduced new modelling by Professor Shaun Hendy and his team at Te Pūnaha Matatina on Wednesday, but the implications were clear.

Like all modelling of this kind, the outcomes should be viewed as estimates with wide margins for error – Hendy and Ardern both stressed this point.

But it reinforces the need to achieve very high rates of vaccination.

In the central forecast, with a 90% vaccination rate of over-fives, the estimated annual death toll would be a fraction of influenza's at just 50.

But if rates fall to 85% with the same moderate public health measures in place, the annual death rate would be an estimated 1,411, close to 1 million people would become infected each year and 38,000 would be hospitalised. At 80% vaccination annual deaths are estimated at 4,936 and hospitalisations at 58,464.

Although the modelling does not directly address the question of lower rates amongst different demographic groups, Ardern was adamant 90% would need to be reached in all ethnicities, age groups and geographical areas.

The race to 90%

So how are we tracking in the race to 90%? On the surface, there are reasons to be optimistic that we will vaccinate 90% of the eligible population.

Since the lockdown began on August 18, 1.5 million people (more than one-third of the eligible population) have received their first dose of the vaccine.

And 73% of the eligible population has now had at least one dose. Throw in a further 4% who have made a booking and 80% is not far away.

It takes 33 days, on average, for the one dose percentage to become the fully vaccinated percentage, so by late-October we should hit 73% of the eligible population fully vaccinated.

And although these figures are for the 12+ population it is safe to assume that they will translate to the 5+. Uptake has been strong amongst 12-15-year-olds since the rollout was extended to them.

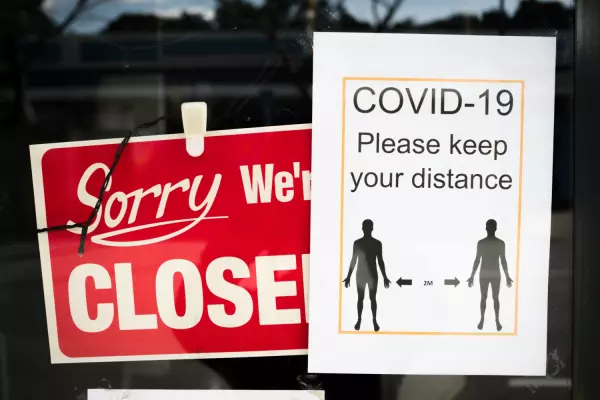

Hitting the skids

However, the rate at which new vaccine recipients are coming forward is beginning to slow.

While we may have moved from 40 to 73% of the population with at least one vaccination (soon to be two) in quick order, moving to the targeted 90% may not be so simple.

All countries eventually hit a plateau in their rollout, and it appears we have found the beginning of ours.

The total number of doses administered will remain high in the coming weeks as the 1.5m return for their second shot. But those people are already locked in, they are going to be fully vaccinated – it's just a matter of time.

It's the willingness of the remaining 1m eligible people without so much as a booking to come forward and receive a first dose that will determine whether we get to 90% and above and how quickly we get there. So watch the first-dose numbers in coming weeks, not the total doses delivered.

Inequitable coverage

Even if we do get there, vaccine coverage across different demographic groups is likely to remain inequitable.

The discrepancies at 73% shows just how far some groups still have to come before an adequate level of protection is achieved.

Above the age of 60, rates are good and there is little discrepancy between ethnic groups, and the Asian ethnic grouping has high levels of coverage at all ages.

Otherwise, as the population gets younger, the vaccine rates decrease and the ethnic discrepancies increase.

Pasifika and, in particular, Māori and those in their 20s have very low vaccination rates.

Twenty to 29-year-olds are the least vaccinated age group in the country. Just 60% have had at least one dose, and for Māori in their 20s, that falls to 35%.

Low levels of vaccination amongst young people are of particular concern in Auckland, where many have this week returned to their service jobs at Level 3.

While rates in Auckland are slightly better, they are still lower for the same groups.

Almost 60% of Māori and half of Pasifika in their 20s in Auckland are yet to receive a first dose.

Persistent gaps

Early in the rollout lower rates for Māori and Pasifika were explained away as a function of age distribution. The Māori and Pasifika populations skew younger and as older age groups were prioritised first we were told to expect a discrepancy which would diminish as the rollout expanded.

But as it has ramped up the inequities between ethnic groups have remained.

More people from all groups are getting vaccinated and that is, of course, a good thing. But the newly vaccinated are disproportionately from those with higher levels of vaccination to begin with, indicating that the under-vaccinated demographic groups are not about to suddenly catch up.

Fewer than one in 10 previously unvaccinated Māori received a first dose of the vaccine in a typical week in September and those rates are falling.

Rates for Europeans and Pasifika are better but are also trending downwards.

The same trend is apparent by age group, with those in their 20s (the least vaccinated age group) also showing the least willingness or ability to come forward to receive a first dose.

The rates themselves are not the issue, so much as the downward trend. For 90% to be achieved in all groups, the downward trend will need to be arrested.

Why it matters

New Zealand may hit 90% vaccination, but on current trends, those remaining unvaccinated will be disproportionately amongst the most vulnerable populations.

And that matters because, as one study found, Māori and Pasifika were twice as likely to be hospitalised with covid-19 than Europeans and were 1.5-2 times more likely to die.

The fact that lower vaccination rates are apparent at younger age groups is offset by the fact that "Māori and Pacific populations ... have a lower life expectancy and tend to experience health issues at a younger age. They also experience greater rates of unmet healthcare needs and greater levels of poverty, which have been shown to have a significant effect on fatality rates.

"For these reasons, Māori and Pacific people are also at higher risk of becoming severely ill and needing to go to hospital as a result of covid-19," the researchers from the universities of Auckland, Canterbury and Otago concluded.

* An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that 1.8 million eligible people were unvaccinated and not booked. The correct figure is 1 million.