OPINION: How RBNZ softened up the banks to accept higher capital rules

It looks like a classic negotiation strategy: hit 'em hard with an extreme-sounding proposition, weather all the flack and pushback, and then finally come out with a "compromise" position that was probably close to what you wanted all along.

So it was for the Reserve Bank's final decisions on how much additional capital the banks will have to carry.

That the end point of a process that began in mid-December last year came as a relief can be seen in the banks' reactions.

"Not so scary," said Bank of New Zealand economist Stephen Toplis. "The consultation was thorough and the concerns of the industry were given a fair hearing," said ANZ Bank's group chief executive Shayne Elliott. "We are pleased the Reserve Bank has engaged with a wide range of stakeholders and made some changes to its original proposal," said the Bankers' Association.

Market pricing told a similar story with the New Zealand dollar lifting a quarter of a US cent and the share prices of all the Australian parents of New Zealand's big four banks rising.

It undoubtedly came as a huge shock a year ago when the Reserve Bank announced it was proposing to force the four major banks to lift their minimum equity from 8.5 percent of risk-weighted assets currently to 16 percent while the smaller banks would have to go to 15 percent.

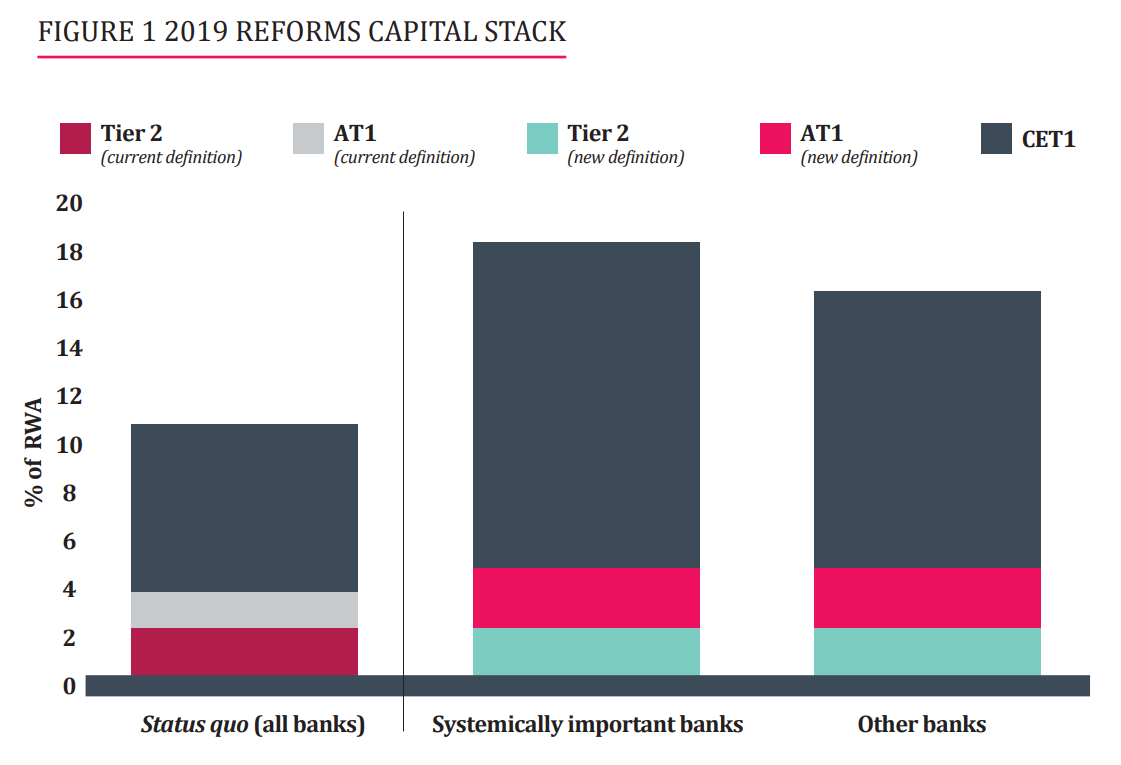

The headline 16 percent for tier 1 capital for the big banks remains, while the small banks will only have to go to 14 percent, but the burden for them all is significantly less because 2.5 percent can be preference shares rather than pure equity.

The Reserve Bank spelt out the difference that makes, putting the cost of equity at 10.56 percent and the cost of preference shares at 7.04 percent.

And the transition period was lengthened to seven years from five with the starting point still more than six months away at July 1, 2020.

ANZ Bank, New Zealand's largest, said it will now need to find about A$3 billion in fresh equity in addition to the NZ$1.5 billion in profits kept in NZ since the proposals were announced.

That's well below its estimate a year ago of A$5.7 billion to A$7.7 billion.

As Kiwibank economists explain, the major banks have an extra two years to meet the new requirement by retaining earnings and will need to only retain 30 percent of profits, rather than 70 percent under the original proposals.

The stretch is considerably less for the smaller banks – three of the four mainstream home-lending smaller banks already held more than 11.5 percent equity at Sept. 30 and SBS Bank at 11.4 percent wasn't far off.

TSB Bank already exceeds the 14 percent tier 1 with equity of 14.6 percent.

On one proposal, diminishing the benefit the big four banks get from using their own internal models to calculate how much capital they need, the RBNZ didn't budge, and that's another reason for the smaller banks to cheer.

The big four will effectively be restricted to limiting the cost saving they get for using their own models to about 90 percent of what they would require if they had to use the standardised models the smaller banks have to use.

That should make the competitive landscape considerably more even.

The Reserve Bank puts the return on shareholders' equity for the large banks at about 15 percent but at less than 10 percent for the smaller banks, although governor Adrian Orr was reluctant to attribute that difference to the leg up the big banks get from using internal models.

But we will all have a much better idea of how big that benefit is because the big banks will have to publish both their capital requirements using their internal models and what the requirement would have to be if they used standardised models.

For all the relief the banks are displaying, the magnitude of the capital changes is still huge.

To put the new NZ rules in context, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority regards equity of 10.5 percent as "unquestionably strong" and the subsidiaries of the Australian banks will be required to hold 13.5 percent.

As Orr said on Wednesday, current capital levels are sufficient to cushion the banks against anything up to a one-in-100-year calamity and the new capital levels will increase that to a one-in-200-year event.

David McLeish, head of fixed income at Fisher Funds, called it "one of the most profound capital reforms in history" and a "gold-plating" of New Zealand's banking system.

"While gold-plating the system might make us all feel safer, it isn't free. It's a bit like insuring your house for twice its value. It does mean you are safe – but you will pay a higher premium each and every year," McLeish said.

The RBNZ acknowledged as much, although it says the changes will add just 20.5 basis points to interest rates which would add $5 a fortnight to the monthly interest on a $100,000 mortgage over 30 years at the current 3.45 percent banks are charging for two-year fixed rate mortgages.

That's well down from the 20-to-40 basis points it had previously estimated and ANZ chief economist Sharon Zollner, for one, is expecting a bigger impact ranging from 30-to-60 basis points, depending on the quality of the borrower.

"There are risks of effects towards the higher end of this range and/or a reduction in the availability of credit, particularly to agricultural and business sectors, reflecting the higher capital required for lending to these sectors," Zollner said.

In effect, lending on mortgages is far less capital intensive than lending to businesses or farmers.

Under the standardised rules, a bank needs just 35 percent of capital to support a residential mortgage with a loan-to-valuation ratio below 80 percent than it needs to support a dairy loan.

International ratings agency Moody's Investors Service says the changes will make the New Zealand banking system more resilient to shocks, but "we expect the new measures will prompt higher lending rates in efforts to boost profitability, as well as constrain growth in more capital-intensive lending."

But the RBNZ insists that it has divined the "sweet spot" at which New Zealand banks are much safer and, rather than detracting from economic growth as it had previously expected, its cost-benefit analysis showed the most likely impact of the new rules is actually a boost of more than 0.4 percent to annual GDP.

Comments