An ageing population, increasingly expensive medicines and high-tech treatments are forcing health insurers to focus on strategies for prevention, earlier diagnosis and shorter hospital stays to keep premiums affordable.

“The system has to change to be sustainable long-term,” says Nick Astwick, chief executive of Southern Cross, New Zealand’s largest health insurer which covers 928,000 of the 1.5 million New Zealanders with health insurance.

As a not-for-profit organisation, Southern Cross pays out about 86c of every dollar in premiums – in the year to June 2022, that came to $1.08 billion, despite the impact of covid-19 on elective treatment.

“Healthcare is not like most consumer markets where technology lowers the cost – it actually increases it. A lot more future treatments are going to be in pharmaceutical businesses which have horrendous price tags and so that risk is real.”

He says precision and personalised medicine also offer the promise of cures rather than treatments, but “we can’t keep growing the price and cost of the current system – it needs to be transformed over the next 10 years".

He says if Southern Cross is to be relevant long-term, it needs a better value proposition – "more health years at a better long-term cost".

"We are working with providers about how the right treatment can be done in the right setting with the right person at the right time.”

A transformation like this will see more patients receiving in-home, rather than hospital, care and insurers will target prevention and earlier diagnosis.

Astwick says private surgery used to mean four or five days in hospital. Now it can be just a day in hospital followed by in-home monitoring and support, delivering better outcomes at lower cost.

“A lot of the cost is in the way private health is delivered, not just technology and surgeon fees. We are putting tension into the system and saying we can’t just keep on paying bills that go up 7% a year. We are a large payer for outcomes. Incentives matter.”

Insurers say the biggest driver of the higher bills is the increasing number of claims, partly as the result of users ageing.

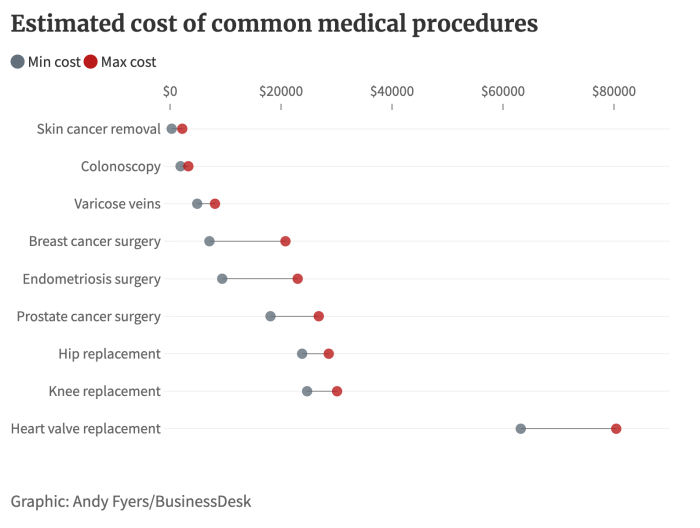

In 2022, for example, nib, the country’s second-biggest insurer, hiked claims for knee replacements by 19% and colonoscopies by 17%, compared with (pre-covid) 2019.

In the past, Southern Cross has put pressure on providers to hold costs, through its Affiliated Provider programme, introduced in 1997. An affiliated provider is a doctor, specialist or medical facility contracted to provide members with healthcare services at agreed prices.

Some providers didn’t sign up to the scheme because it limited how much fees could be reimbursed. Astwick says it’s saved an estimated $200 million on behalf of its members in that time.

Although it caused some angst among doctors in the early years, much of the resentment appears to have gone, in part because of the efforts of Southern Cross’s chief medical officer, Dr Stephen Child, a former chair of the NZ Medical Association, to improve communication with providers.

He says the “riding instructions” in the job he’s had for four years were to bring back the mutual respect that existed between the insurer and providers. He believes he’s doing that but accepts some specialists still don’t like the affiliated provider scheme.

He says a positive of the scheme is that patients walk in and out, and the doctor gets paid instantly.

"The negatives from the doctor’s point of view is that you only get the CPI [Consumers Price Index] increase but health inflation is greater than that, so their costs might go up 4% a year but Southern Cross is only offering 1.3%, so they argue they’re losing money.

He says some medical professionals don’t like the scheme because they believe it limits their ability to grow and be innovative, and to offer high-quality care.

More than 90% of providers have signed up as affiliated providers, and Child says he’s focused on “honest and transparent” communication, advising them of the highest and lowest fees per procedure in their region and where they sit on that scale.

Our ageing population might be akin to a bomb-laden freight train hurtling towards taxpayers, but it’s a rather different equation for the insurance sector. The elderly pay far more for their cover than the young.

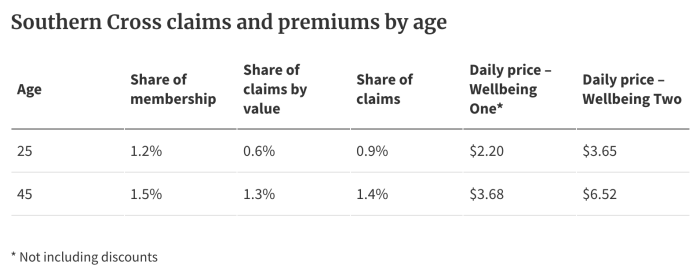

People over 65 claim three times the amount claimed by people aged 39-45, and that’s reflected in their premiums. At Southern Cross, a standard policy will cost $2.20 a day for a 25-year-old and $3.68 for a 45-year-old, compared to daily rates of $17.78 at 65 and $23.81 at 75.

Nib CEO Rob Hennin agrees the ageing population is a threat to the sector.

“Every month, the top 10 claims are generally older people with the big cancer, heart and back operations. They’ve never paid anything like the cost of those with their premiums over their whole lifetime.

"It’s a risk and we try to manage that but it’s a balance because we still need to make sure premiums are affordable for older people.”

In Australia, young and old pay the same rates, and that’s a system Hennin would like to see here, saying it would encourage innovation and competition.

“It would solve the problem for members who find that their prices are going up far too much because of their age or pre-existing conditions, and it would allow them to find an alternative that suits them better.

"Today, because of pre-existing conditions, anybody over 45 is likely to find they really can’t move to another insurer. They have to stay where they are.”

But like the telco and electricity sectors, it’s a change that would need government regulation.

“It’s too expensive for any one insurer to take that risk.”

In Australia, he says, the health insurance sector is “one big risk equalisation pool”. It's managed by government incentives and deterrents encouraging people to be insured because it relieves pressure on the public system.

Insurers with a large proportion of younger members subsidise those with older clients. Nib, whose clientele skews younger, last year paid about A$200m (NZ$220m) into the pool. Despite this, it made a profit of nearly A$134m on revenue of A$2.8 billion.

Nib's Rob Hennnin says the cost of some cancer drugs is "mind-boggling".

Southern Cross figures suggest that insurance “churn” – the number of people who ditch their policies annually – is significantly higher in younger age groups, who presumably see no great value in insurance they're less likely to use.

At 25, 9.5% of customers don’t renew their policies compared with 4.9% of 45-year-olds and 6.4% of 65-year-olds. Prevention and early diagnosis are a key part of the cost containment story, but you won’t find health insurers jumping into screening tests without medical indicators.

“If we did screening for everyone we could be bankrupted pretty quickly or premiums would just fly through the roof,” says Astwick. "In our policies, where a clinician feels like a check, such as a colonoscopy, is medically necessary, of course, that’s in your policy.”

Hennin agrees, saying what’s driving cost increases now is not the higher price of services, but the fact more people are claiming, particularly for diagnostic tests such as ultrasounds, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans and colonoscopies. “It’s volume and in some ways, it’s good volume because it's preventative.”

Nonetheless, Hennin points to the mind-boggling price of some non-Pharmac-funded cancer treatments as an area where costs are growing.

“Of our top 10 claims, four have chemotherapy in them. Two recent claims for leukaemia and breast cancer treatment were close to $200,000 each.

“The price of cancer drugs is the train coming towards us. The public system, particularly for cancer is very, very good but it doesn’t always provide our members with either the access they want or when they want it.”

Last year, Te Aho o Te Kahu (the Cancer Control Agency) found 18 medicines that were funded in Australia but not here that would offer clinical benefits to New Zealanders.

Doctors believe the survival benefits are not necessarily large, but Hennin says having the choice is the important thing for patients.

“These treatments make a world of difference for the person facing that illness and for their family. Of course, there’s the economic lifetime benefit argument but as individuals, we would like choice and we don’t like not having that choice.”

Top claims for procedures by cost:

- Initial specialist consultation.

- Total hip replacement.

- Colonoscopy.

- Total knee replacement.

- MRI scan.

- Spinal fusion.

- Excision skin lesion.

- Chemotherapy treatment.

- Hysterectomy.

Top claims for procedures by volume:

- GP consultations.

- Prescriptions.

- Follow-up consultations.

- Initial consultations.

- Consultations with a physiotherapist.

- Dental consultations.

- X-rays.

- Ultrasound scans.

- Prescription lenses.

- Chiropractor consultations.

In its 10 years in NZ nib has grown rapidly, and now covers 250,000 people. The company bought Tower Medical Insurance with its 18,000 customers in November 2012.

One of its biggest investments in prevention is wellness coaches.

He says about 10,000-15,000 of nib’s clients each year have access to or take part in some form of a wellness programme. Nib employs about half a dozen coaches, but also partners with providers such as TBI Health, a specialist in physiotherapy, rehabilitation and pain and injury management, for group programmes.

The company uses data and analytics to get insights into risk, then proactively offers health management programmes, says Hennin.

The other way of getting access, he says, is by making a claim or getting pre-approved for a procedure. "We will ring you and talk about prehab and rehab. A wellness coach will regularly talk to you after your procedure and make sure you’re getting the care you need.”

Programmes include healthy heart, cancer care, women’s wellness and mental health.

It doesn’t have an affiliated provider scheme like Southern Cross, but nib has set up what it calls the First Choice network. Called a "community of selected healthcare providers", it helps deliver value for members and helps nib manage costs. It covers about 90% of providers.

“Most healthcare providers charge reasonably. We give the outliers the opportunity of coming back into range. We just say if you moderate your prices and come back within range you stay in the network. If not, we will only pay a certain amount and they or the patient makes up the difference.”

CONSUMER INSIGHT

Consumer NZ research suggests customer satisfaction with health insurers is on the wane.

In its 2022 survey of members and supporters with health insurance, only 46% of respondents were very satisfied with the service they were getting, a drop from previous years from 49% in 2021 and 52% in 2020. For the last four years, nib has finished in last place in the survey.

Nib CEO Rob Hennin says their own customer feedback is very positive. He suspects the fact that 80% of nib’s customers pay for their own insurance, rather than being covered by their employers, has skewed the results.

“The structure of our business is quite different to some of our competitors. When you ask a question of someone who’s getting the benefit of a scheme they’re not paying for themselves, they obviously can be pretty happy, but we don’t have a lot of those in our portfolio.”

He says nib is continually improving the way it communicates with customers, moving documentation to “plain English” and improving digital accessibility.

Southern Cross says about 53% of policies are through groups or corporates, but some people pay their own premiums at a discounted amount, while others are fully or partially subsidised by their employer.