He Waka Tapu’s base stands out in the east Christchurch neighbourhood of Wainoni.

The airy reception, with its high industrial ceiling, large windows and pot plants, looks like a trendy workplace lobby.

A woman with a pink buzz cut coming down the prominent wooden stairway holding a baby, and a beanie-clad man clutching a guitar as he waits for a counsellor hint that this is in fact a community provider.

The welcoming space, which includes a small cafe, also serves as an extra waiting room for the general practice operating in He Waka Tapu’s old premises across the path.

He Waka Tapu's main building in Christchurch has a welcoming vibe. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

The organisation is the largest kaupapa Māori social services organisation in Christchurch.

In 2022, it supported more than 7,000 clients with issues including drug and alcohol addiction, family violence and mental health.

Its staff are 90% Māori, working for clients who are at least 80% Māori or Pasifika.

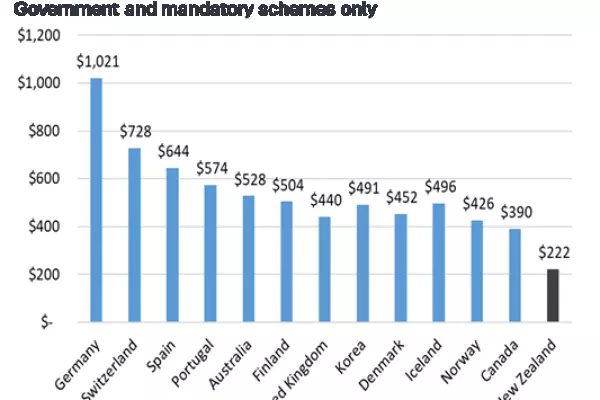

Owner-operators of general practitioner (GP) practices in New Zealand are struggling to stay afloat amid pressures including the increasing demand and complexity of health needs, staffing shortages and increasing costs.

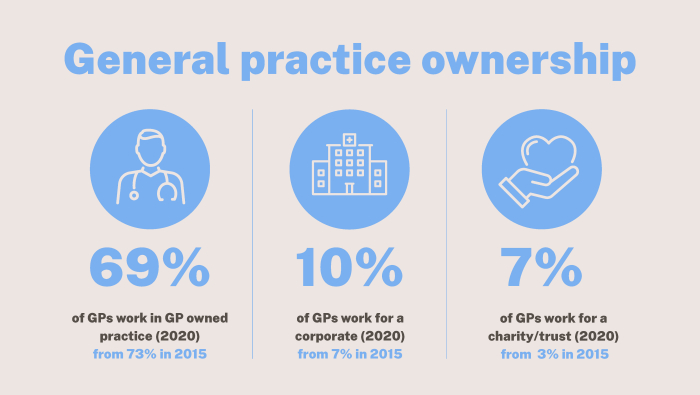

That's why not-for-profit and corporate networks are increasing their ownership.

The percentage of GPs working in community, trust or charity-owned practices has increased from 3% to 7% between 2015 and 2020, according to a Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners survey.

In 2020, He Waka Tapu partnered with the (for profit) Whānau Ora Community Clinic network to set up a GP clinic on its Pages Road premises.

In 2016, George Ngatai, who is leading the network, bought another practice in the neighbourhood from its founder, Paul Hercock, who kept ownership of the building.

But the relationship soured, He Waka Tapu chief operating officer Tanith Petersen said, and in 2021 Hercock and He Waka Tapu evicted Ngatai’s clinics from their premises.

The network shifted its practice to Ngā Hau e Whā national marae across the road from He Waka Tapu.

He Waka Tapu chief operating officer Tanith Petersen says its GP clinic is growing fast. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

Ngatai, who is a Destiny Church member and stood as a candidate for Vision NZ party in the 2020 general election, runs several low-cost GP clinics in Auckland, Northland, Lower Hutt and Christchurch. He also ran covid-19 testing and vaccination clinics during the pandemic.

The network faced legal action last year for its use of the Whānau Ora name and brand (potentially misleading people into thinking the clinics are related to the government commissioning agency).

Hercock, a longstanding and trusted local GP, partnered 50:50 with the Better Health network to restart the other east Christchurch practice in late 2021.

In early 2022, He Waka Tapu joined the partnership and reopened its GP clinic on its premises.

The partnership was going well, but it was difficult to offer patients full support while having to worry about making money, Petersen said.

“I don’t believe you can wrap business and health together and expect great outcomes. But everyone has a place and there is so much need that it wouldn’t be a competition,” she said.

Any money He Waka Tapu makes as an organisation is reinvested toward better health outcomes for everyone, she added.

In November, He Waka Tapu bought out the two other partners in the practice, which it will shift fully to its Pages Rd premises in March.

The fast-growing clinic has 2,000 enrolled patients. The staff includes three GPs, a nurse practitioner, a prescribing nurse and three other nurses. An Auckland GP offers telehealth consultations.

Now the clinic is expected to breakeven in its third year of operation, Petersen said. Official data shows He Waka Tapu received emergency covid-19 funding of $143,000.

He Waka Tapu is the largest kaupapa Māori social services organisation in Christchurch. (Image: Julie Chandelier)

At Te Haranga Health, patients are often seen for longer than 15 minutes. He Waka Tapu members pay a discounted fee of $5; other clients pay the low-cost access clinic fee of $19.50.

But the biggest strength of having a GP clinic as part of a community organisation is that it can offer wraparound support to its patients, who often have complex social and health needs.

A community nurse screens patients for any social needs they might have before they even see the doctor.

Social workers and mental health workers are on site, as well as a free gym, community gardens, a mirimiri (traditional Māori massage) room and a hāngī pit.

“People feel comfortable, respected and welcome here,” Peterson said.

This article has been amended to clarify there was no profit generated from the covid-19 funding.