“The sergeant major of army is often referred to as the senior soldier in our army … an adviser to the chief of army on matters affecting the training, management and welfare of our soldiers,” according to the New Zealand Defence Force (NZDF).

The warrant officer of the defence force “reports to the chief of defence force and is responsible for advising on the morale and welfare of defence people and NCO [non-commissioned officer] professional development across the defence force”.

To civilians, who don’t make a close study of such things, these two ranks may not mean much, but within the defence force, they are crucial roles.

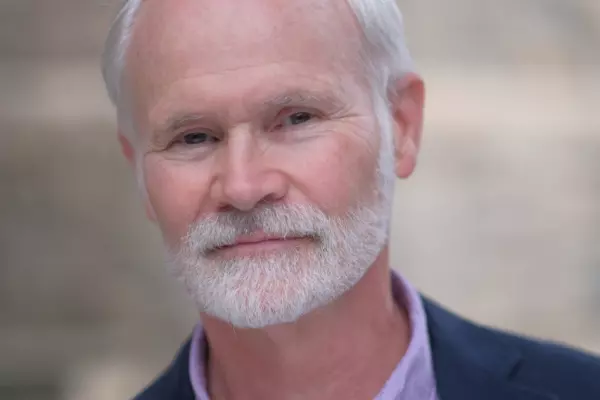

Mark Mortiboy took on the first in 2014 and the second in 2018. He is among the top dozen or so most senior people in our armed forces.

Born in Auckland in 1963 in the last days of the baby boom, Mortiboy is of a generation that tended to change employers frequently. But he has never worked for anyone else, joining the army when he left school with university entrance (UE) at 17.

He cites familiar reasons for the allure of the military.

“I needed discipline,” he says. “I wanted to do something meaningful, something different, have a challenge and adventure and be part of a team with a sense of purpose.”

He found all of that and more, including his nickname “Titch”, an ironic label referring to the fact he is anything but short.

“My late mother told me I was the one who was going to join the military, and specifically the army.”

Also, as he was one of seven children, “I had no dramas about not having a room of my own because I’d never had one".

His ability to inspire others, part of his job today, was obviously close to home.

“Four of my brothers have served. They left school and did other things, but by their mid-20s they had all served – two in the British army and two in the New Zealand army.

“But I was the first, and over the last two years I have become the last.”

At the time he joined, university entrance was not a common qualification, especially on entry into the enlisted ranks.

“The minimum then was the end of fourth form [year 10]. Many others hadn’t had the opportunities I had, and as I served with them I saw they had so much potential.

“One of the beauties of the military is the ability to revisit your education. Many of our people have gone on to get qualifications beyond what they would have expected of themselves.”

Too many fatalities

Years later, his interest in and aptitude for training and caring for colleagues saw him given a task that saved lives.

“We had suffered a string of fatal crashes over a couple of years, all involving the Unimog truck. This brought into question the young age of our military drivers and resulted in a review of all driver training, in which I had a significant role.”

The success of the improved regime resulted in him receiving the Distinguished Service Decoration in 2008. “It was a relatively new honour in the system and I was one of the first recipients.”

Mortiboy continued his own “training” in sometimes surprising ways. His superiors encouraged him to leap ahead and get a Master’s degree, which he did through Portsmouth University in the UK.

His dissertation examined ways the army could better prepare soldiers for transition into civilian life.

Transition and veteran matters are still part of his job, and those he has helped include the likes of possibly NZ’s most famous living soldier, Willie Apiata.

“Few of us really know what we ultimately want to do, especially at the ages we join, but there is so much variety and opportunity as an NCO,” says Mortiboy.

“I had been professing this to others, and part of the thinking behind doing the degree was that I had to set an example.”

Sinai, East Timor & Afghanistan

His studies became a case of military multitasking at its most extreme.

Not only did he have to adjust to academic life after decades, but some of his studies were also done while he was deployed in Afghanistan in 2017. All of it was done remotely, studying online and accessing research material in NZ for supervisors in the UK and, for part of the time, helping out at home with a baby grandson.

This bore out a philosophy he describes as #beallyoucanbe, a lesson he learnt from his father. It underlies most of the work he has done in the Army, including his operational service in Sinai, East Timor and Afghanistan, centring around training.

“The Afghanistan deployment was a single job: to go in and be part of a NATO training group to look at training and educating NCOs in the Afghanistan army.

“It was about preparing Afghan soldiers for challenges they would be likely to face: how to give instruction, how to lead small teams, roles and responsibilities and working alongside an officer.

“They are a replica of our system, although culturally very different.”

He says as a New Zealander, he felt well fitted for this role. “Interaction with other militaries and other cultures gives you the ability to see through the eyes of others. One reason New Zealanders are good at it is an ability to quickly tune into an environment, not least the cultural environment.”

Unscheduled encounters

The combination of all these interests and experience feeds into every aspect of his job today.

He demurs when it’s suggested that his daily schedule must be a packed one, especially given a brief as wide as the handing of “welfare and personnel development matters across the Defence Force”.

“Busy-ness has been a badge of courage,” he says.

“A lot of people say. ‘Excuse me, I know you are busy but … ’

Mark Mortiboy: "I would take the door off my office if I was allowed." (Image: NZDF)

Mark Mortiboy: "I would take the door off my office if I was allowed." (Image: NZDF)“But the role is to circulate, communicate, get around and interact. I deliberately don’t schedule as hard as the chief of defence and others, so I have room for those one-off conversations and unscheduled encounters.

“I would take the door off my office if I was allowed.”

A key aspect is providing a link between the chief of the defence force (CDF) and everyone else.

“Representing our people to the CDF would be the main part of the role. I act as a confidant and provide that perspective to the issues of the day and the decisions that are being made.

“It’s a function that is not widely replicated, to my knowledge, outside of the military.”

It’s an access-all-areas job.

“I have the ability to traverse the whole spectrum of the organisation. I can go down and talk to the most junior officers and NCOs. I can go into the middle and bring that to bear at the top.”

Tough issues

The defence force recognises the importance of supporting both those it employs directly and their families.

“My own family in one sense has served alongside me, and I’m indebted to them for that.

“We send people away from their homes and we are aware of the disruption that occurs.

“Our people are like most New Zealanders. They live in homes and communities in suburbs and they have issues around child care and juggling with what their partners are doing and so on.

“We have to keep those connections strong and see what we can provide in support.”

Bullying, harassment, mental health, suicide – Mortiboy works through all the tough issues.

“We have one of the highest youth suicide rates here in New Zealand, and the military can be reflective of that. We have strong messaging around mental health and support mechanisms, including how to stay on the top of your game.

“The military externally has this view of stigma around showing any form of weakness. ‘Crack on’ and ‘punch through’ and all that.

“People do worry about putting their hand up or having their medical history recorded at the risk of being downgraded.

“One of our big things has been to break that down, having someone like myself say: ‘It is okay to not be okay’ and take the time to talk.”