Apple’s latest software update for iPhones and iPads – iOS 14.5 – now forces apps to ask permission before tracking your movements and habits.

The ‘App Tracking Transparency’ feature gives Apple gadget users the ability to block individual apps from tracking or sharing their data via an automatic prompt – but only when developers comply with the requirement.

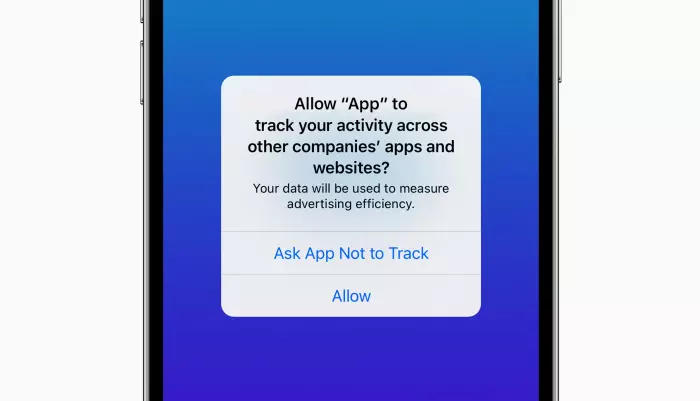

If you have an iPhone or an iPad new enough to update to the software version (2015’s iPhone 6s and 2014’s iPad Air 2 are the oldest compatible), you will soon start seeing pop-ups when you open apps asking if you want them “to track your activity across other companies’ apps and websites?”. You then can either tap ‘Ask App Not to Track’ or ‘Allow’.

The former will stop the app collecting common data points such as location and email addresses and it means the app developer cannot access your data, let alone sell it on.

“The feature is, in my opinion, long overdue,” said Gehan Gunasekara, associate professor of information privacy law at the University of Auckland.

According to him, Apple’s move is directed at how the advertising industry dishonestly monetises personal data.

“These platforms are able to charge a premium for advertising because they know people's lifestyle. They know a lot more about you than you know yourself.”

Online advertising nowadays largely works by identifying you as a user of a certain device and connection location, all while logging your browsing habits, and then selling that ad space.

If you live in Wellington and frequently look at content about sneakers and golf, an advertiser can go to a digital advertising platform and ask to put its ads in front of people in Wellington who like sneakers and golf, and you’ll start seeing those ads pop up, especially on apps such as Facebook.

In theory, tapping ‘Ask App Not to Track’ will curb the accuracy (and creepiness) of targeted advertising.

If you decide to restrict app tracking, it will stop that pair of Nikes you looked at online last week following you around the internet in pop-ups and banner ads.

Apple at the core

Given the proliferation of Apple phones and tablets in the west, this privacy-minded software change has the potential to reshape how advertisers reach people across multiple countries.

“It’s a good thing,” NZ privacy commissioner John Edwards said.

“It makes mandatory what is part of New Zealand law already, that people are told what’s going to happen with their information and give them the right to exercise some autonomy.”

Edwards said that Apple was better placed to enforce such a consumer choice than any NZ regulator.

NZ’s updated December 2020 Privacy Act did not change what data companies can collect on people, but gave New Zealanders an easier path to view the data companies hold on them.

Apple’s original version of its iOS 14 software, released at the tail end of 2020, already had an option to stop apps tracking you, but it was a blanket setting that was not surfaced to iPhone and iPad users.

To find it, go to Settings > Privacy > Tracking and toggle off Allow Apps to Request to Track.

You can also do this in the updated iOS 14.5, as you will have to wait for developers to change their apps to comply with Apple’s new rules before you start seeing the new pop-ups.

BusinessDesk has not yet seen any of the new pop-up prompts on their iPhone since updating to the new software version, and Apple did not respond when asked to clarify how the system works.

Fallout

Facebook has vehemently opposed Apple’s changes because the data the social network giant collects on people is a huge factor in its profitability.

“Platforms like Google and Facebook are making super profits, they're essentially making hundreds of billions of dollars from their advertising revenue, based on essentially spying on people,” said Gunasekara.

“I think the amount of money they’re making from their customers is an unconscionable bargain. It's not a free market, it's essentially a form of expropriation.”

When Apple’s changes first came to light in December, Facebook spun the situation to say it would hit small businesses hardest.

But the reality is that Mark Zuckerberg’s behemoth fears Apple will disrupt its business model, which relies on the blind compliance of its users to share their personal data.

Edwards said Facebook and others who are complaining are overstating the case.

“This is a pretty standard business practice, which is to object to any kind of regulation or constraint on their ability to use data, and then once they fail at that, which they will, they simply pivot and adapt.

“They will go back to making money in ways, hopefully more transparent, and have a more honest engagement with the end user.”

He added that he’ll be interested to see how Google responds. Unlike Apple, which makes iPhones and iPads but does not run a global advertising network, Google maintains both the licensed Android smartphone operating system, its app store, and a global ad network.

“I would like to see them also use that position of power and influence to ensure that people freely enter into these kinds of transactions that trade functionality for data or surveillance.”

Gunasekara went further, arguing that there needs to be a competitive market for personal information where people are financially compensated for the exchange of data they accept from apps and services.

He said a model where people are paid back an agreed percentage of the advertising revenue a company makes from that person’s data is a fairer exchange, suggesting more invasive tracking should mean people are paid a higher percentage.

“It’s a very radical proposition and it won’t go down well in certain quarters,” he admitted.

“But it is long overdue.”