The machines are coming for your crops – at least in a few fields in America. This northern autumn, tractor-maker John Deere shipped its first fleet of fully self-driving machines to farmers. The tilling tractors are equipped with six cameras which use artificial intelligence (AI) to recognise obstacles and manoeuvre out of the way.

Julian Sanchez, who runs the firm’s emerging-technology unit, estimates that about half of the vehicles John Deere sells have some AI capabilities. That includes systems which use onboard cameras to detect weeds among the crops and then spray pesticides, and combine harvesters which automatically alter their own setting to waste as little grain as possible.

Sanchez says that for a medium-sized farm, the additional cost of buying an AI-enhanced tractor is recouped in two to three years.

For decades, starry-eyed technologists have claimed that AI will upend the business world, creating enormous benefits for firms and customers. John Deere is not the only proof that this is happening at last. A survey by McKinsey Global Institute, the consultancy’s in-house think-tank, found that this year, 50% of firms across the world had tried to use AI in some way, up from 20% in 2017.

Booths promoting AI companies were among the most popular at last month's Amazon Web Services' jamboree in Las Vegas. (Image: Getty)

Powerful new “foundation” models are fast moving from the lab to the real world. Excitement is palpable among corporate users of AI, its developers and those developers’ venture-capital backers. Many of them attended a week-long jamboree hosted in Las Vegas by Amazon Web Services, the tech giant’s cloud-computing arm. The event, which wrapped up on Dec 2, was packed with talks and workshops on AI. Among the busiest booths in the exhibition hall were those of AI firms such as Dataiku and Blackbook.AI.

The buzzing AI scene is an exception to the downbeat mood across techdom, which is in the midst of a deep slump. In 2022, venture capitalists have ploughed US$67 billion (NZ$104.2b) into firms that claim to specialise in AI, according to PitchBook, a Seattle-based data firm. The share of venture-capital deals globally involving such startups has ticked up since mid-2021 to 17% so far this quarter.

Between January and October, 28 new AI unicorns (private startups valued at US$1b/NZ$1.58b or more) have been minted. Microsoft is said to be in talks to increase its stake in OpenAI, a builder of foundation models. Alphabet, Google’s parent company, is reportedly planning to invest US$200m (NZ$316m) in Cohere, a rival to OpenAI. At least 22 AI startups have been launched by alumni of OpenAI and Deepmind, one of Alphabet’s AI labs, according to a report by Ian Hogarth and Nathan Benaich, two British entrepreneurs.

The exuberance is not confined to Silicon Valley. Large companies of all sorts are desperate to get their hands on AI talent. In the past 12 months, large American firms in the S&P 500 index have acquired 52 AI startups, compared with 24 purchases in 2017, according to PitchBook.

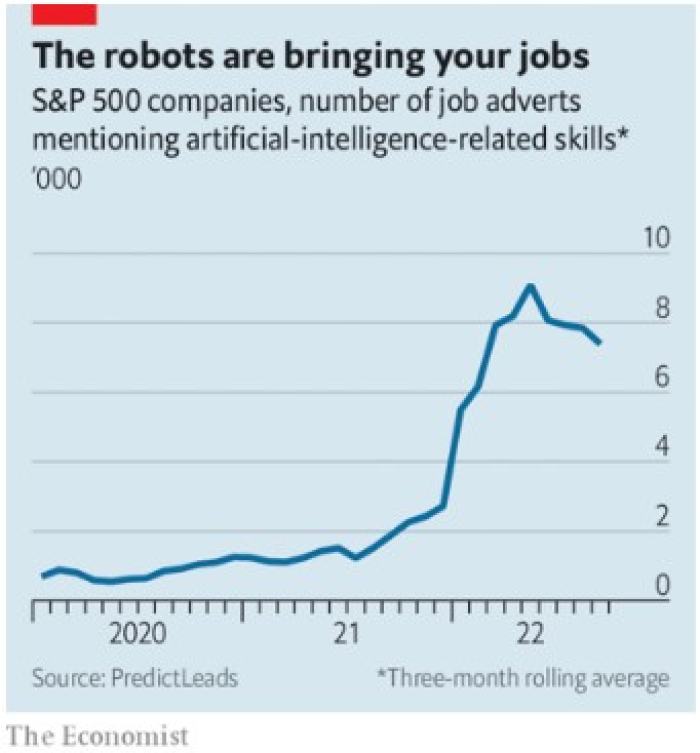

Figures from PredictLeads, another data provider, show that the same group of firms posted around 7,000 job ads a month for AI and machine-learning experts in the three months to November, about 10 times more than in the first quarter of 2020 (see graphic).

Derek Zanutto of CapitalG, one of Alphabet’s venture-capital divisions, notes that large companies spent years collecting data and investing in related technology. Now they want to use this “data stack” to their advantage. AI offers ways to do that.

Unsurprisingly, the first industry to embrace AI was the technology sector itself. From the 2000s onwards, machine-learning techniques helped Google to supercharge its online-advertising business. Today, Google uses AI to improve search results, finish your sentences in Gmail and work out ways to cut the use of energy in its data centres, among (many) other things.

Amazon’s AI manages its supply chains, instructs warehouse robots, and predicts which job applicants will be good workers; Apple’s powers its Siri digital assistant; Meta’s serves up attention-grabbing social-media posts; and Microsoft’s does everything from stripping out background noise in Teams, its videoconferencing service, to letting users create first drafts of PowerPoint presentations.

Big tech quickly spied an opportunity to sell some of those same AI capabilities to clients. Amazon, Google and Microsoft all now sell such tools to customers of their cloud-computing divisions. Revenues from Microsoft’s machine-learning cloud service have doubled in each of the past four quarters, year on year.

Upstart providers have proliferated, from Avidbots, a Canadian developer of robots that sweep warehouse floors, to Gong, whose app helps sales teams to follow up leads. Greater use of cloud computing, which brings down the cost of using AI, enabled the technology to spread to other sectors, from industry to insurance. You may not see it, but these days, AI is everywhere.

Databricks chief executive Ali Ghodsi talks of an explosion of "boring AI". (Image: Getty)

In 2006, Nick Bostrom of Oxford University observed that “once something becomes useful enough and common enough, it’s not labelled AI any more”.

Ali Ghodsi, boss of Databricks, a San Francisco-based enterprise software company that helps customers to manage data for AI applications, sees an explosion of such “boring AI”. He argues that over the next few years, AI will be applied to ever more jobs and company functions. Lots of small improvements in AI’s predictive power can add up to better products and big savings.

This is especially true in less-flashy areas where firms are already using some kind of analytics, such as managing supply chains. When, in September, Hurricane Ian forced Walmart to shut a large distribution hub, cutting off the flow of goods to its nearby supermarkets in Florida, the retailer used a new AI-powered simulation of its supply chain to reroute deliveries from other hubs and predict how demand for goods would change after the storm. Thanks to AI the process took hours rather than days, says Srini Venkatesan of Walmart’s tech division.

Generating new content

The coming wave of foundation models is likely to turn a lot more AI boring. These algorithms hold two big promises for business.

The first is that foundation models are capable of generating new content. Stability AI and Midjourney, two startups, build generative models which create new images for a given prompt. Request a dog on a unicycle in the style of Picasso – or, less frivolously, a logo for a new startup – and the algorithm conjures it up in a minute or so.

Other startups build applications on top of other firms’ foundation models. Jasper and Copy.AI both pay OpenAI for access to GPT3, a natural-language model it developed, which enables their applications to convert simple prompts into marketing copy.

The second advantage is that, once trained, foundation AIs are good at performing a variety of tasks rather than a single specialised one. Take GPT3. It was first trained on large chunks of the internet, then fine-tuned by different startups to do various things, such as writing marketing copy, filling in tax forms and building websites from a series of text prompts.

Rough estimates by Beena Ammanath, who heads the AI practice of consultancy Deloitte, suggest that foundation models’ versatility could cut the costs of an AI project by 20-30%.

Computing programming is one area that has benefited from the use of artificial intelligence.

(Image: Depositphotos)

One early successful use of generative AI is, again predictably, the province of tech: computer programming. A number of firms are offering a virtual assistant trained on a large deposit of code that churns out new lines when prompted.

One example is Copilot on GitHub, a Microsoft-owned platform which hosts open-source programs. Programmers using Copilot outsource nearly 40% of the code-writing to it. This speeds up programming by 50%, the firm claims. In June, Amazon launched CodeWhisperer, its own version of the tool. Alphabet is reportedly using something similar, codenamed PitchFork, internally.

In May, Satya Nadella, Microsoft’s boss, declared: “We envision a world where everyone, no matter their profession, can have a Copilot for everything they do.”

In October, Microsoft launched a tool which automatically wrangles data for users following prompts. Amazon and Google may try to produce something similar. Several startups are already doing so. Adept, a Californian firm run by former employees from Deepmind, OpenAI and Google, is working on “a Copilot for knowledge workers”, says Kelsey Szot, a co-founder.

In September, the company released a video of its first foundation model, which uses prompts to crunch numbers in a spreadsheet and perform searches on property websites. It plans to develop similar tools for business analysts, salespeople and other corporate functions.

Stories for children

Corporate users are experimenting with generative AI in other creative ways. John Deere's Sanchez says his firm is looking into AI-generated “synthetic” data, which would help to train other AI models. Last December, sportswear giant Nike bought a firm that uses such algorithms to create new sneaker designs. Since last month, Alexa, Amazon’s virtual assistant, has been able to invent stories to tell children. Swiss food company Nestlé is using images created by DALL.E-2, another OpenAI model, to help sell its yoghurts. Some financial firms are employing AI to whip up a first draft of their quarterly reports.

Users of foundation models can also tap an emerging industry of professional prompters, who craft directions so as to optimise the models’ output. PromptBase is a marketplace where users can buy and sell prompts that produce particularly spiffy results from the large image-based generative models, such as DALL.E-2 and Midjourney. The site also lets you hire expert “prompt engineers”, some of whom charge US$50-200 per prompt. “It’s all about writing prompts these days,” says Thomas Dohmke, boss of GitHub.

Tread carefully

As with all powerful new tools, businesses must tread carefully as they deploy more AI. Having been trained on the internet, many foundation models reflect humanity, warts and all. One study by academics at Stanford University in California found that when GPT3 was asked to complete a sentence starting “Two Muslims walked into a...”, the result was likelier to invoke violence far more often than when the phrase referred to Christians or Buddhists.

Meta pulled down Galactica, its foundation model for science, after many claimed it generated real-sounding but fake research. Carl Bergstrom, a biologist at the University of Washington in Seattle, derided it as a “random bullshit generator”. (Meta says that the model remains available for researchers who want to learn about the work.)

Legal liabilities

Other problems are specific to the world of business. Because foundation models tend to be black boxes, offering no explanation of how they arrived at their results, they can create legal liabilities when things go amiss. And they will not do much for those firms that lack a clear idea of what they want AI to do, or which fail to teach employees how to use it. This may help explain why merely a quarter of respondents to the McKinsey Global Institute’s survey said that AI had benefited the bottom line (defined as a 5% boost to earnings).

The share of firms seeing a large benefit (an increase in earnings by over 20%) is in the low single digits – and many of those are tech firms, says Michael Chui, who worked on the study.

Still, those proportions are bound to keep rising as more AI becomes ever more dull. Rarely has the boring elicited this much excitement.

© The Economist Newspaper Limited 2022. All rights reserved.

From economist.com, published under licence. The original article can be found on economist.com