Compass Group NZ, wholly owned by a British-based multinational public limited company, supplies thousands of meals a day to New Zealand's hospitalised, elderly and vulnerable.

Proportionally for Compass, its New Zealand contracts are small fry.

It’s the world’s largest contract food services provider, employing around half a million people and serving more than four billion meals a year.

In Aotearoa, it has more than 4,000 staff working at locations all over the country.

As well as medical facilities, Compass has contracts to serve at Air New Zealand lounges, Fonterra sites, military bases, police cafes, elderly care homes and university halls of residence.

Most recently, in 2020, it was awarded a contract to supply 11,600 daily free school lunches.

Within the NZ health sector, Compass is the largest food supplier. It has contracts with 12 Te Whatu Ora districts.

In late 2014, six District Health Boards (DHBs) collectively signed a 15-year deal with the multinational company, known as the Food Services Agreement (FSA).

Yet many regional health decision-makers have chosen to turn away from the global giant.

One district told BusinessDesk after ditching Compass, it saved millions of dollars, kept 99% of its staff and now serves higher-quality food.

Healthy margins

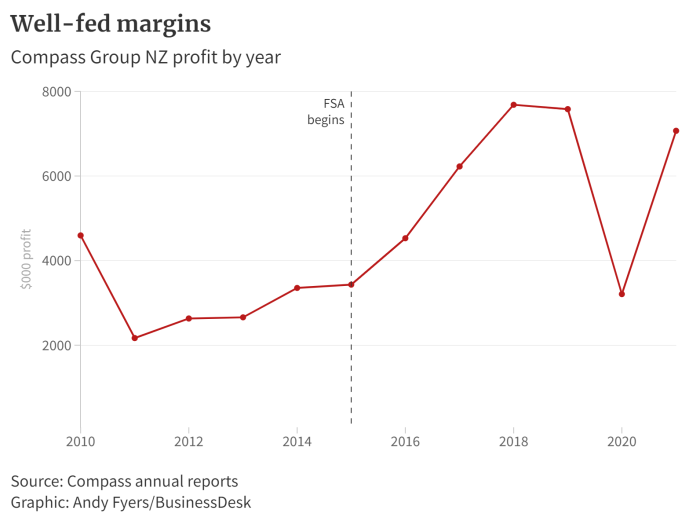

Between 2010 and 2021, Compass NZ has taken in $2.2 billion in revenue and turned $55 million in profit.

The agreement was a significant boost for Compass. Between 2015 and 2018, its annual profits more than doubled from $3.4m to $7.6m.

This growth was reversed in 2020, when profits sank back to $3.2m. However, Compass experienced a swift recovery the next year, with margins back to pre-covid levels; an annual growth in profit of 120%.

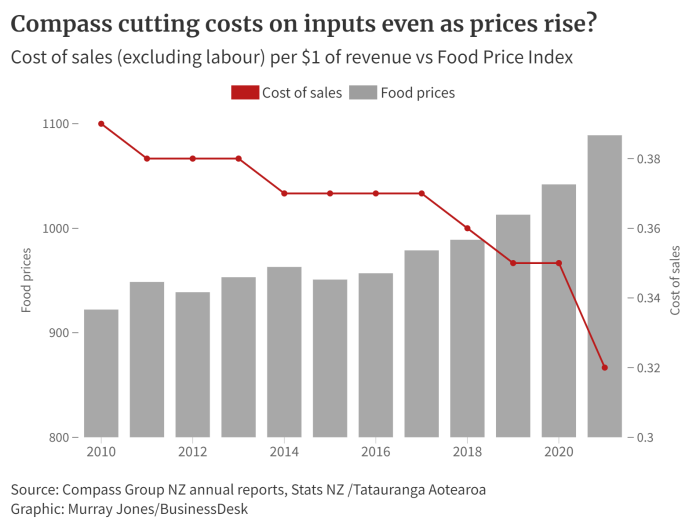

Impressively, Compass has successfully shielded itself so far from the rising prices of food and fuel.

Its cost of sales, excluding staff pay, to generate a dollar of revenue has been on a steady downward march over the past decade, from 39 cents to 32c per dollar of revenue – an 18% saving.

This is despite food prices in NZ increasing every year since 2016.

Nearly half of these savings came in 2021, a year when food prices in December were 4.5% higher than the year before.

Conversely, in that same 12 months, Compass NZ's employee costs per dollar of revenue increased 8.5% from 47c to 51c.

When asked, Compass Group NZ refused to say whether this had been achieved by buying cheaper ingredients.

However, in a May interview with Reuters, global chief executive Dominic Blakemore admitted it had reduced menu choices, switched to cheaper ingredients and reduced the protein content of meals to save money.

Both Te Whatu Ora and Compass refused to release total figures spent nationally on food for the health sector or any figures suggesting the average cost per meal or per patient per day supplied by Compass, saying the information was commercially sensitive.

However, Compass introduced a 5.5% price increase in just the second year of the agreement, followed by a 3.5% rise the following year.

NZ Health Partnerships, the collective body that signed the agreement, has so far delayed the disclosure of the increases for the subsequent years.

Auckland district revealed it spends $17.2m a year with Compass. Southern paid an average of $9.4m between 2017 and 2021.

In Auckland, there was an average of 566 patients in bed per day or 206,000 bed days in the year 2018-19.

The sum paid to Compass also includes payment for the Meals on Wheels programme and cafeteria services, so a per-meal cost estimate isn't possible.

Te Whatu Ora did reveal that, as part of the food service agreement, Compass serves 3.5-4 million meals a year, depending on occupancy levels, which is 0.1% of Compass’s global output.

Despite this, in its latest annual report, parent Compass Group highlighted the “double-digit growth” in New Zealand as one of the key reasons for its Rest of World division achieving 3% organic revenue growth.

Asia Pacific director, Mark Van Dyck wrote: “Our performance was also helped by the business mix we have built and especially a higher concentration in the offshore & remote, and healthcare sectors, which were both less impacted by the pandemic and traded consistently above 2019 throughout the year.

“We expect demand for quality outsourced food services to increase. With our scale, flexible operating model, enhanced digital capability and our team expertise, we are excellently positioned to capitalise on these opportunities.”

Value for money?

Compass didn't get off to a great start with the food services agreement.

According to RNZ, the firm got dozens of complaints over ‘disgusting’ food being served at Dunedin Hospital in 2016, which even led to protests outside the facility.

But has food quality improved since then, despite less being spent per dollar of cost to the DHBs?

Zara Wilson stayed in the Palmerston North maternity ward in November 2021 for a week-and-a-half.

She told BusinessDesk the food was “horrendous”, adding: “The portions of the large meals were palm-size and again not enough to sustain a new mum trying to bring in her milk supply.

"The fish pie was bad enough to make me want to vomit. It was definitely not fresh and resembled cat food.

“I actually ended up spending a fair bit of money ordering Uber Eats and getting family to bring me in frozen homemade meals as I could not eat what was served.”

We put Wilson's story to Compass, which said: “We are deeply concerned by the feedback you shared about the new parent in Palmerston North. We were not made aware of this and sincerely apologise that her expectations were not met.

"We welcome feedback in any instance where one of our meals is not to someone’s satisfaction, as this gives us an opportunity to investigate and improve our service. As you would expect, we have food safety and quality controls in place to maintain the quality of our meals.”

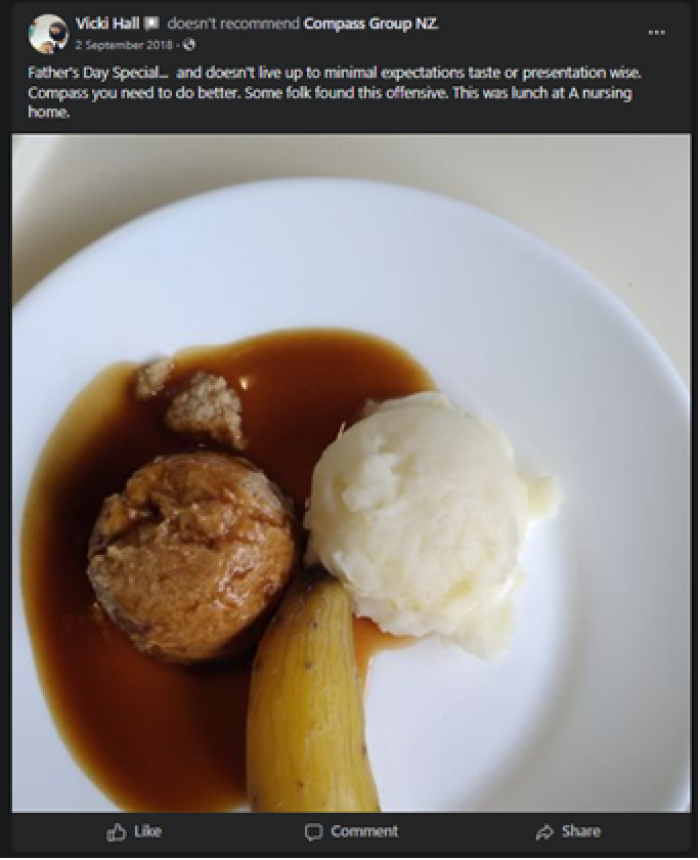

An unimpressed visitor posted on Compass' Facebook page a photo of a lunch served at a nursing home on Father's Day. (Image: Facebook, Vicki Hall)

‘Most heartless employer’

In NZ, Compass kitchen staff are part of the E tū union. Negotiations are under way for a new pay deal.

Reviews left by workers online list issues with underpayment, late payment, pressure to accept overtime with no incentives, high staff turnover and inappropriate cooking facilities for serving large numbers of people.

In the UK, Compass subsidiary ESS was labelled the nation’s “most heartless employer” by the UK’s second-largest union over a policy that threatened workers with termination if they refused to sign a new contract that would make them up to £1,600 (NZD$3,091) a year worse off.

Last year, Compass was forced to apologise to thousands of British children after its lunch parcels were dubbed ‘poverty picnics’ by campaigners, including footballer Marcus Rashford.

The scandal erupted after a mother posted a picture of the parcel with a paltry selection of food, including two carrots, two potatoes and a small range of other food items. The packages were supposedly worth £30 ($57.96) but were estimated to only contain £5 worth of food ($9.66).

Just a month before, the NZ Ministry of Education announced that Compass had won a contract, along with five other suppliers, to supply lunches for six school districts (New Plymouth, South Taranaki, Feilding, Whanganui-Rangitikei, and Christchurch 1 + 2).

In a statement to BusinessDesk, Compass Group NZ suggested it may continue to increase prices for customers.

“Like all local and global businesses, we’re now facing inflationary pressures ... which puts pressure on our business as we remain committed to delivering a quality service and value for money.

“Our team, scale and experience is an important attribute in managing this. We’re also having conversations with our customers about the potential impact of these increasing costs.

“We are confident that we are providing quality food to hospitals across Aotearoa New Zealand within each district's available budgets. We are also proud of our patient satisfaction ratings that consistently exceed 90% across our network."

It acknowledged its customers have a choice of inhouse food preparation or outsourcing food services.

“The feedback that we receive is that our customers choose to outsource so that they are able to focus on their core business/service; they are able to provide a more consistent and quality of food service; they have flexibility; they don’t have to deal with challenges of unavailability of staff, or staff shortages; they don’t have to invest in food service infrastructure, equipment and ongoing maintenance and they get better value for money."