This is part two of a special series on clinical trials: read more here.

The global reputation New Zealand gained for its covid control has proven a multimillion-dollar boon for our clinical trials industry, with one of its big players saying the sector has tripled in value.

The country has three main private clinical trials companies: the Pacific Clinical Research Network (PCRN), NZ Clinical Research (NZCR) and P3 Research. All have attracted significant private equity investment in recent years, enabling further expansion.

A paper published by the NZ Institute of Economic Research in 2020, covering 2013-18, estimated clinical trials of new medicines were worth more than $150 million a year to the country.

But that’s an underestimate now, says P3 managing director Professor Richard Stubbs, a retired academic surgeon who bought into the company in 2005 and later took it over with colleague John Calder, the former chair of Wakefield Health.

“Based on what we’ve observed, you could fairly reliably say the industry today would be [worth] three times that.”

In December, P3’s seven-site business secured investment from Genesis Capital, with Stubbs retaining 10% of the company.

“When covid hit, the entire world was made aware of NZ because it was doing such a good job at stopping people dying,” he says.

“New Zealand was on the lips of the pharmaceutical industry the world over, even those parts of the industry that had never heard of us. In most places, clinical trials had to stop. In New Zealand, they were able to keep going.”

PCRN founder and medical director Dr Mike Williams agrees. “The world went bonkers during covid. Medical services around the world had never met such a challenge.

"Drug development basically stopped – 80% of our business that was about to start at the time of covid stopped. It was unknown whether you’d be able to see patients and have them come in on site.

"The massive university hospital sites got smashed to bits, staff-wise, resource-wise, and because of their inability to see patients with everyone in quarantine.

"But in New Zealand, because we didn’t get the initial [disease] surges, we didn’t get our medical system being smashed. Even with lockdowns, trials in some cases were able to continue because we could still see our patients safely.”

Pacific Clinical Research Network director Mike Williams says covid was good for NZ's clinical trials industry. (Image: PCRN)

He says in one global study during the pandemic, for a new cough medication, PCRN’s Rotorua site was the only one in the world able to see patients on site within the trial’s timeframe.

PCRN’s 16 sites are mainly linked to general practices, which he says recognises the power of primary care.

“You should put a clinical trials unit where the participant is comfortable getting their care, and that’s in a primary care facility in the community, not an ivory tower where people have to pay for parking and walk for 45 minutes down some corridor and be seen only between 8am and 2pm.

"Our participants can park outside, they’re comfortable with the surroundings, they know where to go, they might be familiar with the staff and it’s much less of a barrier.”

Williams became involved in clinical trials “by accident” in 2002 when pharmaceutical company GSK approached a number of GP practices, including his, asking them to take part in an asthma study. Eight years later, he and his wife Philippa founded Lakeland Clinical Trials after being offered a six-figure contract for a 200-patient trial of a flu vaccine.

In October 2021, Pencarrow Private Equity took a 52.4% stake in PCRN, which was formed by bringing together Lakeland Clinical Trials, and Christchurch-based Southern Clinical Trials, set up by GP Dr Simon Carson and his partner, Julia Mathieson.

That investment is funding the next stage of PCRN’s growth, into phase 1 trials.

Phase 1 trials are the first phase of human testing, in which drugs are used in very small doses on limited numbers of patients to test whether they are safe. Phase 2 and 3 trials test for a drug’s efficacy, including comparisons with existing medications.

PCRN is building a 1,300-square-metre unit for phase 1 and later phase trials in Fred Thomas Drive on Auckland’s North Shore, due to open in July.

The “state-of-the art” 24-bed facility will be the company’s flagship. P3 is also looking to open a phase 1 unit in Wellington, using the money from the Genesis investment. Stubbs says the 20-30 bed unit, like a small private hospital, is about a year away.

Before now, phase 1 trials have been the almost exclusive territory of NZCR. Like PCRN, it was formed after clinical trials groups in Auckland and Christchurch, the first set up in the south by nephrologist Professor Richard Robson, joined forces about four years ago.

Investment by Waterman Private Capital in September 2020 has enabled the company to significantly expand, doubling the size of its Christchurch unit, creating two new centres in Hamilton and Wellington and increasing the size of its unit in Auckland by 30%.

Williams says the growth of the private sector is changing the model of clinical research, moving it away from the days when it was the domain of public hospital or university-based “key opinion leaders”, whose reputation would attract the big drug companies.

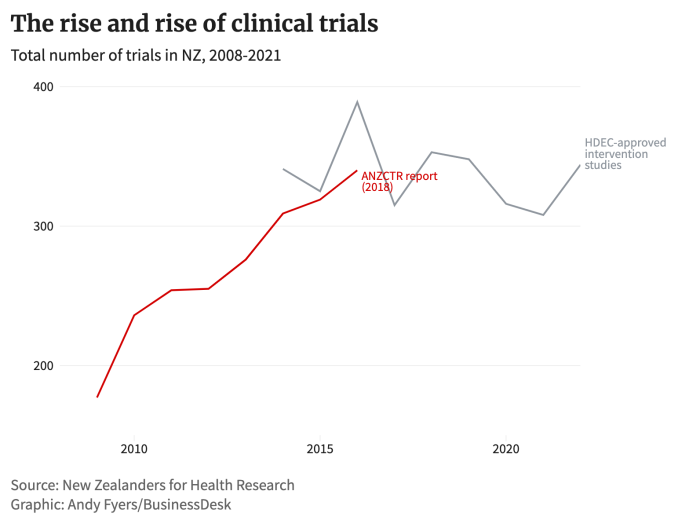

The resurgence in clinical trials follows a dip from the late 1990s to the mid-2000s following the establishment of Pharmac in 1993, after which a number of big drug companies wound up their NZ operations, including their research and development arms.

“Some of the big commercial players lost interest in running clinical trials in NZ because they weren’t seeing the potential for sufficient returns because of Pharmac’s purchasing and rationing policies,” says Chris Higgins, chief executive of health advocacy group New Zealanders for Health Research.

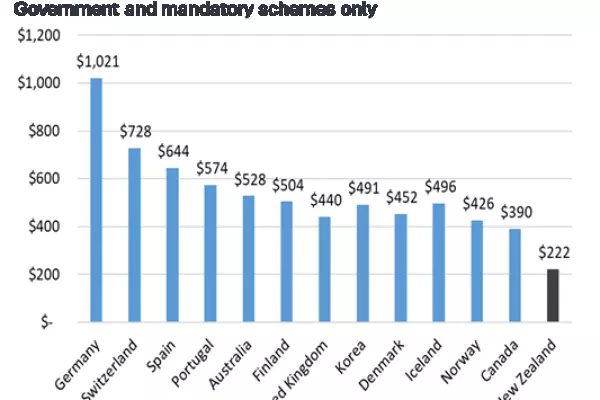

Figures gathered by the group show trials activity has picked up steadily since 2008. (See graph above.)

“I think some of the pharmaceutical companies have decided to get over themselves, because NZ is actually a good place to conduct clinical trials.”

Higgins says there’s widespread public support for clinical research. A poll of 1000 participants commissioned by the group last year found about 70% are willing to participate in research and want more opportunities to take part in trials.

One of the companies which did stay on post-Pharmac is Merck, one of the global “big 10” companies, which spends $10 billion annually on research internationally.

In 2022, Merck spent $4.96 million on research in public and private institutions here – much of it involving its blockbuster cancer immunotherapy drug Keytruda – a big increase on the $3 million it spent in 2019.

Clinical research director Scott Bannan says given 70% of its research is in oncology, much of it has to be done in public hospitals for access to complex cancer cases and specialist oversight.

The venture capital investment in the private research companies is a recognition of both the potential of the industry to bring that work to NZ, and the skill with which they perform, he says. “We work with all of those guys, and they are really good performers.”

In the public health sector and institutions such as universities, however, it’s acknowledged that we could be doing better.

A report released in July 2022 led by Liggins Institute director Professor Frank Bloomfield said our health system generally did not have a strong research culture, “notwithstanding individual examples of excellence”.

“Health system decision-making often does not facilitate research activity and, in many cases, can be a barrier to research.”

Outside the Health Research Council, clinical trials which benefit New Zealanders and reduce inequities are rarely prioritised and clinical research workforces are “fragile”, the report said.

Few trials had been conducted in Māori health provider settings and none in Pacific provider settings and there is a need for the work to be more responsive to Māori needs, and more sensitive to cultural requirements.

But there are promising signs of change. Research and clinical trials are now part of the Service Improvement and Innovation directorate at Te Whatu Ora where respected investigator Dr Robyn Whittaker was appointed in February as director of evidence, research and clinical trials, to strengthen and enhance research and innovation in health services.

Te Whatu Ora’s Dr Dale Bramley, national director of improvement and innovation, says its collaborating with Manatū Hauora (Ministry of Health) to address the recommendations in the Bloomfield report.

NZ Clinical Research's Chris Wynne says there's little point dealing with the government. (Image: NZCR)

NZCR’s chief scientific officer Dr Chris Wynne believes that until now a lack of will, as well as a lack of capacity, has limited growth of trials in public hospitals.

“They could contract to an organisation like ours to run their trials infrastructure and they could invest in running their own infrastructure that would generate a return for them, but they are so busy delivering clinical work in a stressed environment that clinical research is not their focus," says Wynne, an oncologist.

"What the hospitals don’t understand is that they see it as a cost to them, but there are some studies where the drugs in the comparator arm of the clinical trial would be provided free by the drug company for the patients and at the moment the hospital is paying.

“There are lung cancer patients in Australia who have access to modern medicines and the only way we can give those patients access [here] is to put them into a clinical trial but the oncologists are so busy they can’t find time to run them."

Australia’s clinical research industry also has the benefit of a tax rebate of about 43% on clinical trials costs offered to companies that make less than $20 million a year. Industry leaders say they’ve been pushing for similar tax relief in NZ, to no avail.

Wynne is critical of his interaction with the government so far.

“I had a phone call from someone at the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment asking if they could set up an appointment to talk to us to work out how early phase clinical trials work in NZ because they had funding to assist an Australian company to come to NZ and grow the industry.

"My response was, ‘You’re asking to pick my brains so you can spend my taxpayer dollars to bring in a competitor?’ We don’t deal with the government – there’s little point.”

Dr Meghan McIlwain, president of the NZ Association of Clinical Research, agrees tax incentives are key. “Overall, NZ is a highly desirable destination to conduct clinical trials. We have competitive study start-up times, a diverse patient population and a strong track record of patient recruitment and retention. Our sites produce high-quality data.”

But to remain attractive to trials sponsors, she says NZ needs to provide tax incentives, embrace new technology to help patient recruitment and retention, expand the clinical trials workforce and ensure start-up times remain short.

She and other industry leaders say NZ’s relatively rapid clinical trials approval process of only about six weeks, through ethics committees and Medsafe, might be at risk if there are changes in the Therapeutic Products Bill, which has been referred to the health select committee.

One of the bill’s stated aims is to make clinical trials regulations “more robust”. During covid, she says, NZ was a “gem” on the international clinical trials stage.

Malaghan Institute director Graham Le Gros says homegrown institutions need clinical trials capacity (Image: NZME)

Professor Graham Le Gros, director of Wellington’s Malaghan Institute, which has been running its own clinical trials for 30 years, says it’s also critical for homegrown institutions to have clinical trial capacity to develop their own drugs. Malaghan is now doing clinical trials of its own CAR-T cancer therapy and covid vaccines.

“We are trying to make it available to communities that may not be interested in a highly specialist medicine done in big hospitals – we have to do clinical trials here to understand what our communities and our people want.”

He says local trials benefit patients, clinicians and the wider population.

“They give NZ patients access to cutting-edge new drugs which would take many years, if at all, to come here.

"You could save more NZ lives. They expose our clinicians, nurses and trials staff to overseas best practice, so it becomes state-of-the-art for the new ways of, say, treating cancer. And thirdly, it raises awareness of the health system so you get an educated population.”

Richard Stubbs sees only growth ahead.

“There are more trials every year and the sum of money spent on them is growing internationally. It’s a huge number because the future of the pharmaceutical industry depends on the development of new medications.

"If it has no R&D [research and development] or new medicines, it will die.

"The medical world is looking for more and better answers for more and more things."

This story has been updated to correct an incorrect figure supplied to the Companies Office.